Your blog

”For years, I’ve been explaining to people that daily blogging is an extraordinarily useful habit. Even if no one reads your blog, the act of writing it is clarifying, motivating and (eventually) fun.” — Seth Godin

The popularity of Mastodon and ActivityPub encouraged many people who didn’t want to join a large instance like Mastodon.social to spring up their own instance, just for themselves and friends. Niche instances have a more usable “local” timeline, where you can see just posts from the small number of users on that instance.

The Portland-based conference XOXO started their own Mastodon instance XOXO.zone just for conference attendees. Six Colors founder Jason Snell started his own instance Zeppelin.flights just for himself and friends in the Apple community.

Some of these smaller instances will become great communities. It’s an important part of finding our way out of the mess of massive social networks to embrace smaller social networks, so smaller Mastodon instances should be encouraged. But some instances are just experiments.

I noticed one day that the Zeppelin.flights instance that Jason Snell used to run was no longer online and I asked him why he had shut it down. He told me it was simply that people stopped using it. And because he was paying a hosting company to run the server, he didn’t want to pay for it anymore.

I think that is common. You sometimes see Mastodon instances simply go away, or people move to a new Mastodon instance, which changes their username. The fediverse feels a little fragile because most Mastodon users are using someone’s instance without thinking much about their long-term identity on the web.

Later, as the chaos with Elon’s takeover of Twitter was causing users to move to Mastodon, Jason brought Zeppelin.flights back online. More people were ready to use it, and he could jump back into the fediverse with the same domain name. That’s the value of owning your own space.

Mastodon prioritizes a federated network. Micro.blog takes a hybrid approach: distributed where it’s most important, content on your own site at your own domain name, but centralized where we can make it easier to use.

People are always looking for a Twitter alternative. When they think they might have finally found a viable one, they get excited.

It’s useful to go back to why I’m working on Micro.blog. In my Kickstarter video, I said:

I know that clones of Twitter and Facebook have come and gone, but something was missing before. And today’s social networks have new problems. Hate and harassment are too common. Fake news and lies spread too easily. The time is right for a new approach.

Let’s break that down. It’s specifically three things:

- Twitter clones usually don’t last. The path is always the same: usage spikes at the beginning, an interesting community forms if you’re lucky, and then it fades away. For Mastodon not to follow the same course, there has to be something different about it.

- Twitter has new harassment problems. Massive, centralized social networks are broken. Mastodon’s distributed nature presents an opportunity and challenge for solving this. The capability to disconnect entire instances will likely split the federation into multiple communities.

- Twitter popularity is a double-edged sword. Retweets amplify posts to a larger audience, which is often a good thing but sometimes discourages more thoughtful posts. Mastodon is mostly a feature-to-feature clone of Twitter. While Mastodon purposefully avoided quoted tweets, it still has favorites, reblogs, trends, and some of the popularity contest ramifications.

Micro.blog’s approach instead starts with blogs. Rather than trying to recreate Twitter with a more open or distributed platform, the idea is to build Twitter-like functionality on top of existing blog platforms like WordPress. You don’t need to run your own instance of Micro.blog.

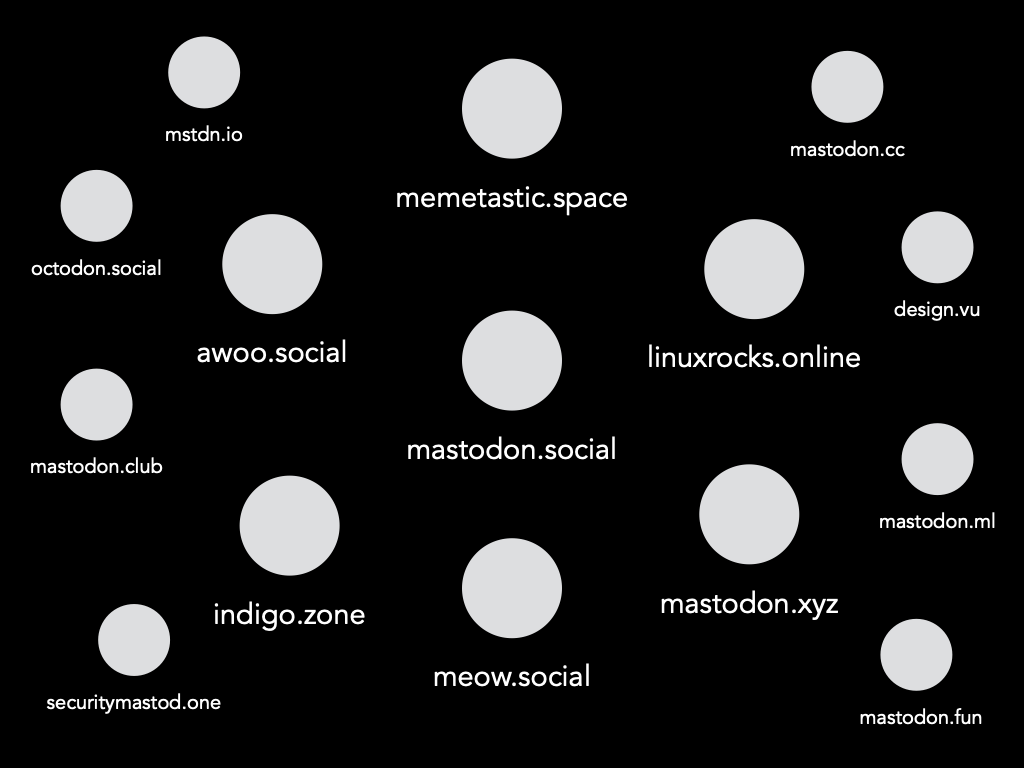

With Mastodon, you usually have of a mix of Twitter-like instances based on ActivityPub, each one holding many users, often thousands. Here is a sample of federated instances:

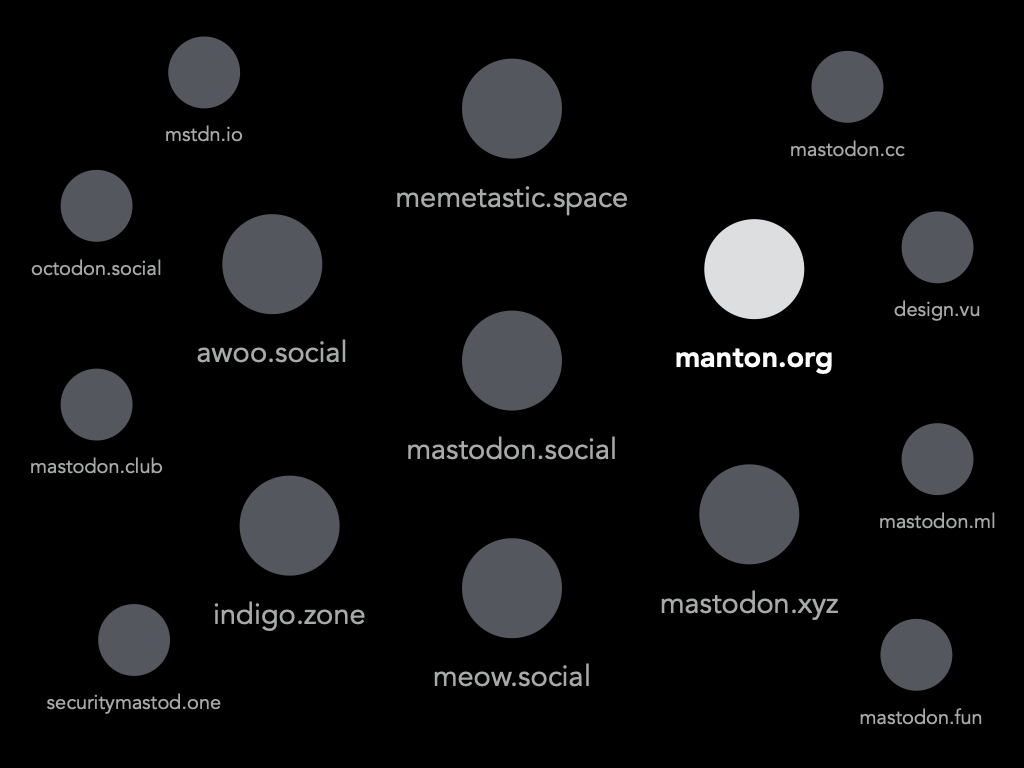

But what I really want is just me. Instead of multi-user instances, a more distributed web should contain many solo instances, each a blog for just one person with their own domain name:

Remember, most Twitter clones fail. With the platform based on blogs, the worst case if Micro.blog doesn’t work out is that you’ve still got your own blog! Instead of being left with nothing, you have all your microblog posts, domain name, and design. You can still cross-post to other social networks and move on to the next thing without starting over.

This is how the web was supposed to work. We’ve gotten away from it and now it’s time to find our way back. The IndieWeb has long been working toward this.

Remember that the difference between domain.com/username and username.domain.com reveals a lot about how a service thinks about the web. Having a hostname or custom domain name means you own your content and can move it. I wish Mastodon had opted for @username.domain.com replies instead of @username@domain.com, so that it could naturally evolve to simply @manton.org.

On the second issue quoted from Kickstarter above, of managing hate and harassment, I knew this had to be planned for from the beginning. That’s why it was my stretch goal and why I’ve been working with Jean MacDonald to guide the community. There is more about Micro.blog’s unique take on balancing openness and safety in Part 6.

Mastodon has solved some technology problems and it has had great traction. I’m impressed with what developer Eugen Rochko has done with it.

But I’m just as interested in many things that Mastodon doesn’t attempt to solve. Not just the technical issues, but especially around human behavior and empowering people — building UIs that encourage a great community, and tools for publishing that are tied to personal domain names and portable into the future. Micro.blog starts with that as its foundation.

If we want to keep our primary identity on our own blog, do we need to throw away the progress that Mastodon has made, cutting off our blog from everyone on Mastodon? No. By adding ActivityPub to blogging platforms, we can get compatibility for posts and replies with other Mastodon users, without running a Mastodon instance ourselves.

Micro.blog has built-in support for ActivityPub. After you’ve added your own domain name to your microblog, Micro.blog presents an option to enable ActivityPub support. Click Account from Micro.blog on the web and scroll down to the ActivityPub section. You can pick your own username at your own domain name:

Now anyone on Mastodon can follow your blog by using your-username@your-domain.com. When they reply to your posts, the replies will appear in the Micro.blog timeline. Setting up ActivityPub in Micro.blog also lets you follow anyone on Mastodon, because to other Mastodon instances it looks like your blog is like a single-user Mastodon instance.

Your Mastodon-compatible username on Micro.blog is independent of any actual Mastodon instance. You can’t use it to sign in to Mastodon or use Mastodon apps. Instead, you can search for Mastodon users inside Micro.blog and reply to posts, and Mastodon users can follow your Micro.blog account and reply to posts as well. Your posts on Micro.blog can show up in Mastodon’s federated timeline.

To follow a Mastodon user on Micro.blog, click Discover on the web and look for the search button:

Then enter a full Mastodon username in the search box:

As more Micro.blog users interact with Mastodon users, some of those users will naturally show up in conversations or even be featured in our Discover timeline.

There are other options for Mastodon-compatible usernames, but with a focus on blogging. Pleroma bills itself as a “lightweight” fediverse server. Microblog.pub is a single-user microblogging server you can run yourself. Bridgy Fed takes a similar approach to Micro.blog, gluing ActivityPub support into an existing blog.

For WordPress, there’s a plugin to enable ActivityPub on your blog, allowing people to follow your blog from Micro.blog and Mastodon, and hooking into WordPress’s comment system for replies. Matt Mullenweg views ActivityPub as an important enough technology that Automattic hired the plugin’s developer, Matthias Pfefferle, to work on improving the plugin full time.

In a blog post about the IndieWeb and the fediverse, Ben Werdmuller wrote that he was moving away from cross-posting to other services, instead keeping the focus on his own site, now that he can participate in the larger world of Mastodon instances:

I want my site to connect to the indieweb; to the fediverse; to people who are connecting via RSS; to people who are connecting via email. No more syndication to third parties. My own website sits in the center of my online identity, using open standards to communicate with outside communities.

ActivityPub is now widely deployed and makes a great addition to most blog platforms, as long as there’s a solid foundation first with personal domain names, feeds, and IndieWeb standards.

Moving more to blog-based solutions for ActivityPub and the fediverse also helps with the separation of content away from platform silos. As we cover more in Part 6, even the most wrong-headed ideas sometimes need their own space on the internet. What they don’t need is to be shouted from the rooftops and echoed among followers in a social network’s algorithmic timeline.

Note that content amplification is not only technical. Substack has tried to walk a difficult line between their clearly expansive free speech beliefs and the need to moderate hate speech.

On one hand, their platform is well-suited to separating what content they will host from what they will promote. Authors can have a blog and email newsletter, largely writing about any crazy ideas they want without getting in too much trouble, as long as it’s not featured by Substack. It’s terrible content off hidden in the corner of the platform, not easy to discover.

But because Substack is also facilitating subscription payments for authors, this creates a new tension that does not exist in platforms that don’t have a way to monetize content.

Substack co-founder Hamish McKenzie wrote about their decision to allow Nazis to continue to publish on Substack:

We believe that supporting individual rights and civil liberties while subjecting ideas to open discourse is the best way to strip bad ideas of their power. We are committed to upholding and protecting freedom of expression, even when it hurts.

Because of the money, this goes beyond just “supporting” open discourse. Substack is effectively helping amplify authors' voices through indirect funding. By allowing them monetize their content, Substack is helping fund it.

Next: WebSub →