Bridgy

“So come and walk awhile with me and share the twisting trails and wondrous worlds I’ve known. But this bridge will only take you halfway there. The last few steps you have to take alone.” — Shel Silverstein

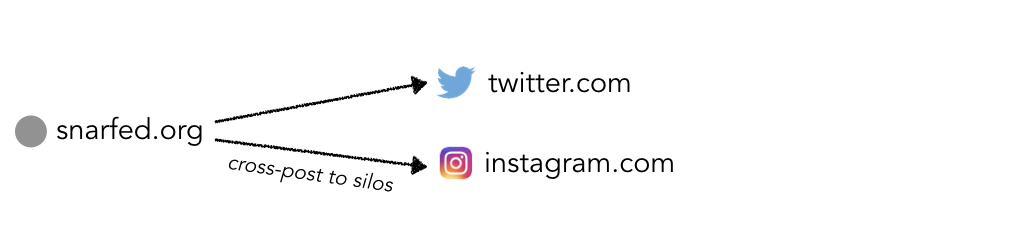

POSSE is a popular part of the IndieWeb community. Cross-posting lets us stay connecting with friends on other silos like Twitter.

Bridgy was developed by Ryan Barrett to help “bridge” the gap between our own blogs and silos. If you’re cross-posting your blog posts to Twitter, Bridgy can check for replies or likes to those tweets and then send them back to your blog via Webmention.

By checking for interactions from silos, friends can reply using existing platforms they are used to, but you still see those replies on your own blog.

When you register on Bridgy, you give it your blog and your account at a silo like Twitter. It checks your Twitter account for replies to your blog posts. If your cross-posted blog posts have a link back to your post in the tweet, Bridgy can match that to your blog post and send a Webmention using the content in the reply on Twitter.

How is this possible, when tweets only exist on twitter.com and photos might be on instagram.com, not individual domain names with the appropriate Microformats markup? Bridgy creates shim web pages with the contents of the tweet reply marked up appropriately. It’s the URL for those special web pages outside of Twitter or Instagram that Bridgy sends to the Webmention endpoint.

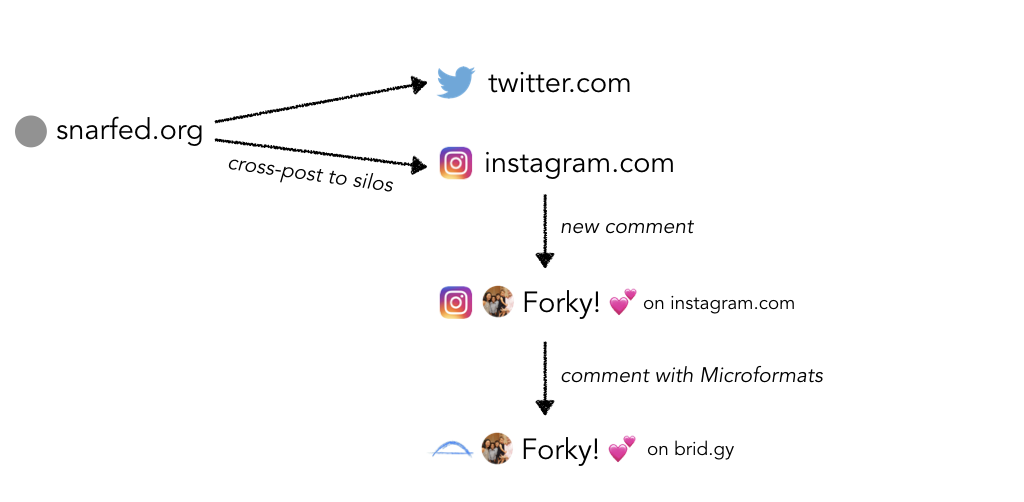

Let’s use an example of this flow from Bridgy developer Ryan Barrett’s posts. His domain name is snarfed.org and his Instagram username is @snarfed.

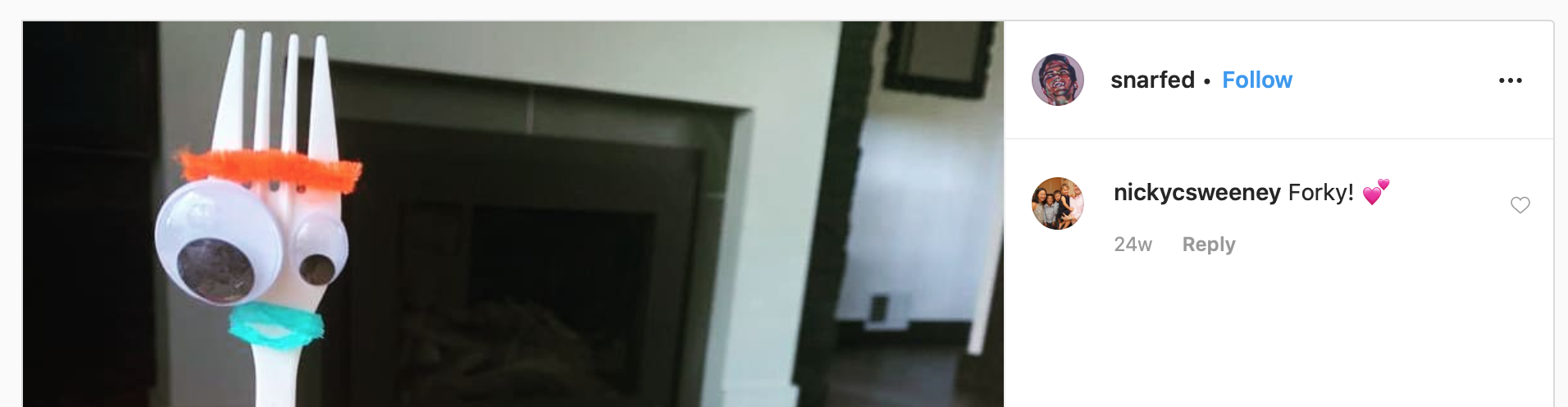

First, he posts a photo of Forky from Toy Story to his blog. He copies the post over to Twitter and Instagram, too.

Someone adds a comment to the Instagram post:

Bridgy is polling Twitter and Instagram, looking for replies and likes on that post. When it finds the comment on Instagram, Bridgy creates a small HTML page with the contents using Microformats.

It then sends a Webmention back to Ryan’s blog, notifying the blog of this new comment, with a URL for the version of the post in Bridgy with Microformats. Ryan’s blog can then update with the reply directly on the blog post:

The IndieWeb has a term for this process of pulling replies and likes from silos: backfeed. It also allows you to curate the conversations because there’s a copy on your web site:

You can moderate those as you see fit on your own site, thus improving the comments overall on your posts as compared to what silos allow for.

On a silo, you have limited control over what content appears alongside your own posts. On your own web site, harassing or misinformed replies can be removed.

Micro.blog has limited support for replies from Twitter, Mastodon, Instagram, and Bluesky via Bridgy. If you were using Bridgy to connect your blog to Twitter, Micro.blog had initially been ignoring any tweet replies to your blog post. Unlike for Micro.blog users, Mastodon users, and blogs, there was no way to represent a Twitter user in Micro.blog, and so it didn’t make sense to thread tweets into a Micro.blog conversation.

Everything in the Micro.blog timeline needs to come from someone’s blog, where the username is either a Micro.blog username or a domain name. Twitter and Instagram users do not have a unique domain name, because they are all shared under “twitter.com” or “instagram.com”.

Including tweets in Micro.blog would have other ripple effects that I wanted to avoid. For example, what happens if you reply to a tweet? I’m not interested in turning Micro.blog into a Twitter client. Quite the opposite. I’m actively trying to distance myself from Twitter and avoid dependencies on any big social networks.

Bridgy is so popular in the IndieWeb community, though, that I revisited this limitation. Micro.blog will now recognize Twitter and Mastodon usernames sent via Bridgy and store those replies in Micro.blog. Twitter users will still not appear in the Micro.blog timeline, but they are available for querying from the API, or including on your own blog hosted by Micro.blog.

As Twitter has continued to shut down their API under Elon Musk’s leadership, most services including Bridgy have had to disable support for Twitter, making this largely a moot point in 2024.

Micro.blog has a built-in JavaScript include called Conversation.js for showing replies on a blog post. It pulls these replies from a conversation on Micro.blog, plus any Twitter replies from Bridgy. This brings Micro.blog’s Webmention support more in line with what Webmention.io can provide.

Because Micro.blog-hosted blogs are just blogs, with themes that allow you to customize any of the HTML, it’s possible to swap out Conversation.js with another solution. If you edit your blog to use a separate service to collect incoming Webmentions, like Webmention.io, then replies to your blog post will go to that service. You can then display any type of Webmention on your Micro.blog-hosted blogs, even those from Bridgy.

There’s an additional gotcha you should know about using Bridgy and Micro.blog together. Bridgy needs a link to your blog post for it to be able to match up tweet replies to that blog post. When cross-posting to Mastodon, Bluesky, and other services from Micro.blog, Micro.blog only includes a link back to your blog if your blog post has a title, or if it needs to be truncated to fit in the tweet.

If you want all cross-posted tweets to link back to the microblog post, even if they were short, you have a couple options:

- Use Bridgy itself for the cross-posting instead of Micro.blog, and disable cross-posting in Micro.blog. Many cross-posting services will always include a link back to your blog.

- Use a Micro.blog theme that has special support for adding the

u-syndicationmicroformat with blog posts. When Bridgy crawls your blog, it can use this syndication link to match up the post on an external service.

Bridgy can find replies on Bluesky for your blog posts. Because Bluesky uses domain names for usernames, it’s a perfect fit for how Micro.blog thinks about the web. When someone on Bluesky replies to your post, Micro.blog will receive a webmention from Bridgy. Micro.blog then adds the reply directly to the timeline, creating a new user if necessary to represent the Bluesky account.

Micro.blog has also been expanded to support following some Bluesky users. It uses a combination of RSS feeds from Bluesky with Bluesky’s AT Protocol API to retrieve profile information.

If your blog is using Micro.blog, there are Hugo parameters you can use to insert the cross-posted URL in theme templates. The following parameters are supported by Micro.blog:

.Params.twitter.id— tweet ID.Params.twitter.username— your Twitter username.Params.medium.id.Params.medium.username.Params.linkedin.id.Params.linkedin.name.Params.mastodon.id.Params.mastodon.username— just the username part of your full handle.Params.mastodon.hostname— instance name like “mastodon.social”.Params.tumblr.id.Params.tumblr.username.Params.tumblr.hostname— you.tumblr.com.Params.flickr.id.Params.flickr.username.Params.bluesky.id.Params.bluesky.url— the “at://” URL for the post.Params.bluesky.handle.Params.bluesky.hostname.Params.bluesky.did.Params.nostr.id.Params.nostr.pubkey

When posting to your blog, Micro.blog follows this basic flow:

- Updates your blog with the new post.

- Downloads your JSON Feed which now contains the new post.

- Sends a copy of the post as a cross-post to Bluesky and other services.

- Updates the blog post metadata to store the URL or post ID from the external service. For Bluesky, this is in the form of an

at://scheme. - Publishes your blog again now that it has this new metadata, so the Hugo parameters are available.

Here’s an example of including a link to Bluesky in the blog post. Note that in this case I’m hiding the link using display: none in CSS. This still allows crawlers such as Bridgy to find the information. You can choose to include links or icons to other services.

{{ if .Params.bluesky }}

<a class="u-syndication" {{ printf "href=%q" .Params.bluesky.url | safeHTMLAttr }} style="display: none;">Also on Bluesky</a>

{{ end }}

Because of how Hugo escapes HTML attributes, we have to do this little dance with printf so the value is escaped correctly.

Looking at the Bridgy shim web pages can illustrate how Microformats can enhance the content on a web page. Twitter’s own HTML is complicated, with a mix of CSS and JavaScript. But Bridgy’s version is simple.

Black before Twitter started closing their API, I posted a test tweet reply to one of my own blog posts. When Bridgy noticed the reply tweet, it created a new shim web page at a URL that included the tweet ID:

https://brid.gy/comment/twitter/mantonsblog/1395021416588849153/1395033801533927428

The important part of the HTML at that web page looks like this:

<article class="h-entry">

<span class="p-uid">tag:twitter.com,2013:1395033801533927428</span>

<time class="dt-published" datetime="2021-05-19T15:09:11+00:00">2021-05-19T15:09:11+00:00</time>

<span class="p-author h-card">

<a class="p-name u-url" href="https://twitter.com/mantontest">Manton Test</a>

<a class="u-url" href="https://www.manton.org/"></a>

<span class="p-nickname">mantontest</span>

<img class="u-photo" src="https://pbs.twimg.com/profile_images/851438000349134849/tkIzJz0b.jpg" />

</span>

<a class="u-url" href="https://twitter.com/mantontest/status/1395033801533927428">https://twitter.com/mantontest/status/1395033801533927428</a>

<div class="e-content p-name">

This is a test reply to see <a href="http://Brid.gy">Brid.gy</a> in action.

</div>

<a class="u-in-reply-to" href="https://micro.blog/"></a>

<a class="u-in-reply-to" href="https://twitter.com/mantonsblog/status/1395021416588849153"></a>

<a class="u-in-reply-to" href="https://www.manton.org/2021/05/19/webmention-and-twitter.html"></a>

</article>

It includes everything needed to show the tweet outside of Twitter — such as p-author with a profile photo, and e-content for the tweet text — along with metadata to follow the conversation thread back to the original blog post, like u-in-reply-to.

Simple formats are easier to understand and combine with other services to build something new.

Next: Blog archive format →