Part 5: Decentralization

“To bring in someone from Berkeley, I had to change chairs to another terminal. I wished I could connect someone at MIT directly with someone at Berkeley. Out of that came the idea: Why not have one terminal that connects with all of them?” — Bob Taylor

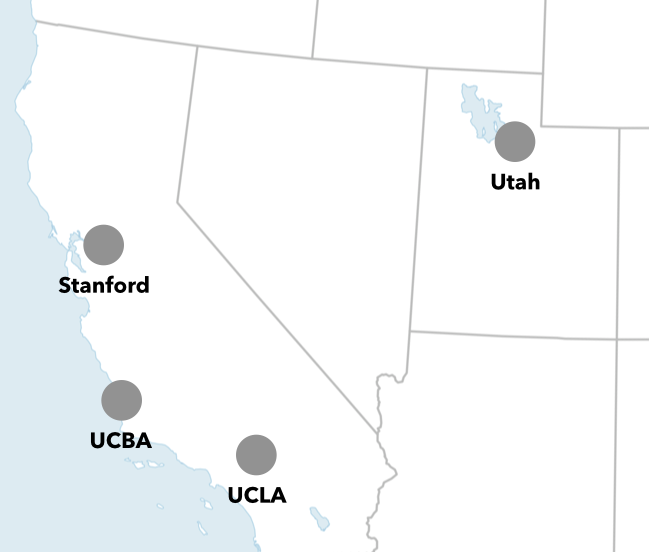

ARPANET was a government-funded network started in 1969 to connect government and university sites across the United States, and the precursor to the internet. Initially it was just a few nodes, from the University of Utah to research centers in California.

Expanded in the 1970s and 1980s, ARPANET adopted the TCP/IP protocol used today and allowed for networks within the larger ARPANET, first spanning to Hawaii and Europe, and then everywhere. By the early 1990s, even before the invention of the web, file-sharing protocols like FTP and systems like Usenet were in widespread use.

And because sending data between networks was still slow compared to a file transfer on the local network, it was common to mirror important files between locations so that there would be extra copies closer to whoever was downloading them. Students could access the files they needed quickly on the campus network instead of reaching across the internet to other servers.

Long-time Apple developer James Thompson was on Jeff Veen’s podcast Presentable, episode 78, looking back on what it was like distributing Mac shareware in the early 1990s:

We uploaded software to this thing called the Info-Mac Archive. You emailed a copy of your software to it, and then it got replicated across the internet. So there was an Info-Mac Archive mirror in… Usually most of the major universities around the world would host one, and some of the companies and things. And it meant that there was somewhere close to you that you could download your software from.

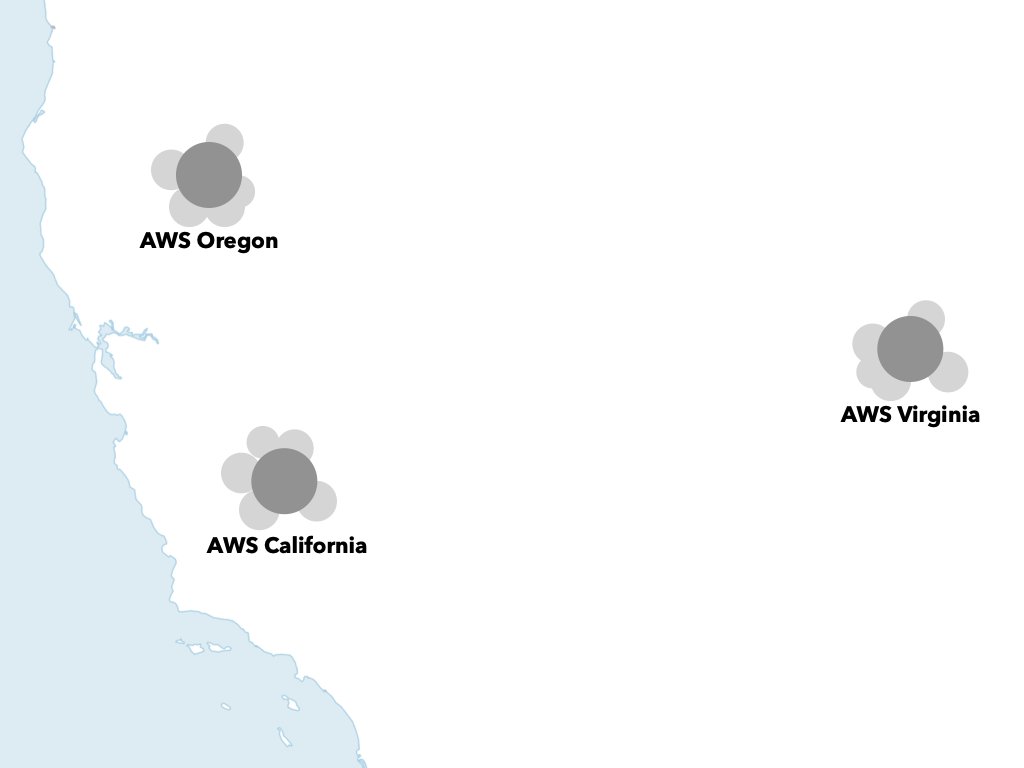

The scope of today’s internet by comparison is so massive it is hard to grasp fully. Instead of a few servers in a university basement, a single data center might hold thousands of servers.

While the data for monolithic platforms like Facebook is spread across the globe using content-delivery networks, putting photos and other common downloads closer to users, the data centers are controlled entirely by that platform. The early Info-Mac Archive servers were much more open, distributing control over each mirror to the local operators so they could make the best decisions for their local users, or anyone connecting from the internet.

The Usenet system was transparent and open. Modern content-delivery networks are opaque and keep all the power with the platform provider.

Data centers are still getting bigger. Martha Harbison writes for The New York Times about “hyper scale” data centers:

Hyperscale data centers (each at least 100,000 square feet in size) run the internet, and they’re growing like gangbusters, both in number and size. A year ago, there were 449 hyperscale centers in the world; today there are 504, with the biggest topping out at millions of square feet. A conservative estimate for their total footprint is 125 million square feet, roughly the size of 2,170 football fields. One square yard of one of those “football fields” holds 1 petabyte of data: 250,000 DVDs worth.

It would be worrisome if all content on the web was stored in a single massive, centralized data center, but despite how big Amazon Web Services is getting, there isn’t any risk of that happening. The physical map of the web — where servers are located, and how they’re distributed — isn’t something most of us have control over anyway.

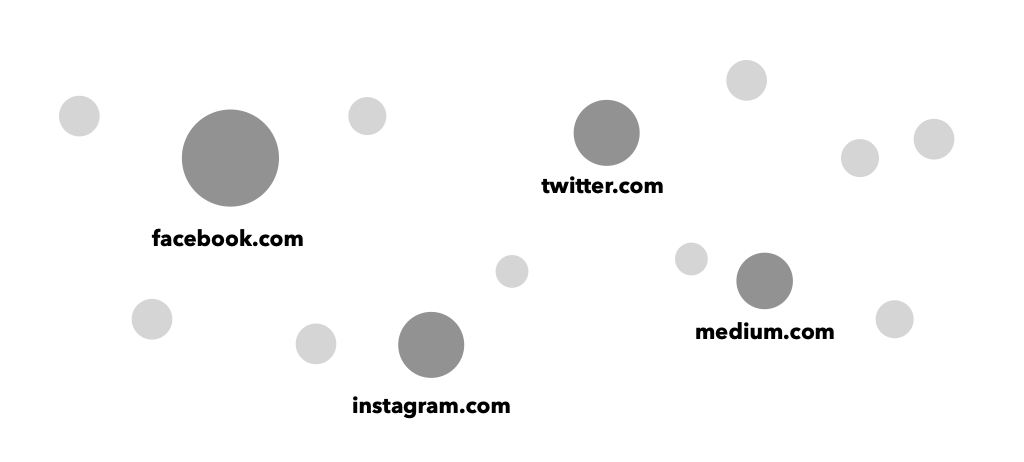

The conceptual map of the web is different. We can wipe away the physical map, leaving dots on the map for domain names instead of physical servers. This is something that is directly shaped by our choices. If too many people use silos, the web becomes more concentrated around those silos.

If more people use domain names, the web naturally becomes more distributed.

Federation is a middle-ground that starts to split centralized servers — a step on the way to full distribution. Instead of everyone’s content living on a large silo, smaller groups of people can share a server. Multiple servers can talk to each other.

There are also social networks that push the distribution even further, to more of a peer-to-peer model like Planetary, based on Scuttlebutt:

…it works by not one company or database holding all the information, but it’s spread out and held by all your friends, and each of our computers.

Nostr likewise has no centralized server, instead relying on a series of relay servers. Posts are copied to multiple servers, and clients will sync up with whatever servers they are configured to connect to. As long as your post is still stored on at least one relay server, it can be found and available to followers.

Nostr uses WebSockets, a protocol built on top of HTTP for web clients to have a persistent connection to servers, allowing them to get real-time notifications when a new post appears without occasionally polling the server.

But Scuttlebutt and Nostr are a bit on the fringe of social networks. New, fully distributed protocols are hard for people to wrap their head around. The decentralized project that has managed to wrap all the right pieces together is Mastodon.

Mastodon is the most popular decentralized social network. In a way, it’s not unlike those early Usenet systems of mirroring files. When you post on Mastodon, your post is copied to other Mastodon instances so that it’s available to followers on other instances. Mastodon is powered by the ActivityPub protocol that is used to communicate between Mastodon servers.

There has been so much traction with Mastodon and ActivityPub that in the coming years we should expect even much larger platforms to adopt it. Flipboard and Meta’s Threads both started experimenting with ActivityPub support in late 2023.

It’s okay to have some number of centralized platforms, although for indie microblogging we should always prefer small platforms. Micro.blog itself mixes centralized elements — a single place to start your blog and follow blogs in a timeline — with the inherent distribution of domain names. It then layers on federation by being compatible with Mastodon.

Next: Notifications →