Microformats

“The world isn’t run by weapons anymore, or energy, or money. It’s run by little ones and zeroes, little bits of data.” — Cosmo from Sneakers

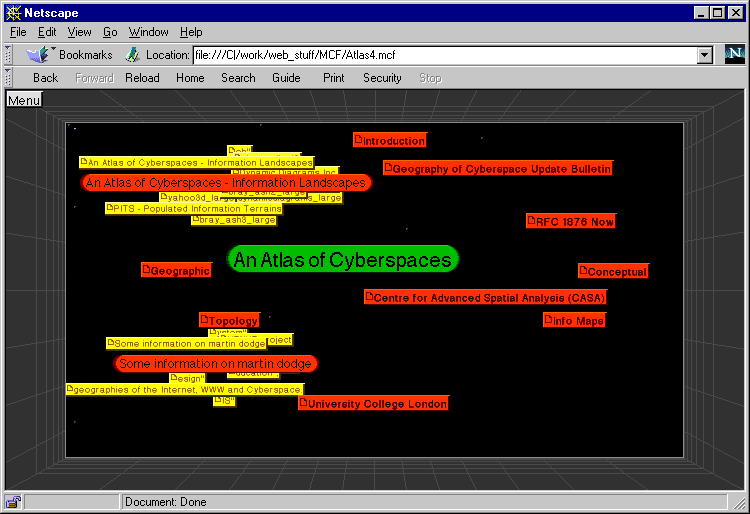

In January 1996, I gave a conference presentation with my friend Travis Weller about a web server framework we had written inspired by MCF. MCF stands for Meta Content Framework and was led by R.V. Guha, who worked at Apple at the time, creating a tool called HotSauce for visualizing nodes of data in MCF. HotSauce even got stage time at Macworld. It was this popularity through Apple that Travis and I noticed.

MCF looked like a transformational step forward for the web. I was young and excited and ready to believe in the future. Years later these ideas would evolve to become RDF — the Resource Description Framework — and encouraged by the W3C:

RDF extends the linking structure of the Web to use URIs to name the relationship between things as well as the two ends of the link (this is usually referred to as a “triple”). Using this simple model, it allows structured and semi-structured data to be mixed, exposed, and shared across different applications.

RDF was the basis for RSS 1.0. At the launch party for Creative Commons, Aaron Swartz explained the value of RDF this way:

Right now you can only ask a search engine one question: “What pages have these words in them?” When pages include RDF metadata, you will be able to ask more advanced questions like “What’s the current temperature in California?”

There were great people like Aaron working on this, but RDF and the so-called Semantic Web haven’t lived up to our original expectations.

Even some early advocates had become doubtful. Tim Bray wrote in 2003:

The RDF version is harder to read, harder to write, and doesn’t offer enough payback to make this worthwhile.

It tends to trade away real-world progress today for a more complicated vision of the future that always seems illusive. Even ActivityPub, which has growing support thanks to Mastodon, seems unnecessarily burdened by JSON-LD, a sort of JSON flavor of RDF.

The “LD” in JSON-LD stands for “linked data”. RDF and JSON-LD attempt to add structure and meaning to web pages and APIs. With the types of data and relationships between documents more fully described, computers could in theory query the entire web as a database, answering our questions or sharing data between services.

Tim-Berners Lee, James Hendler, and Ora Lassila co-authored a paper for Scientific American in 2001, laying out this vision for the Semantic Web:

The Semantic Web will bring structure to the meaningful content of Web pages, creating an environment where software agents roaming from page to page can readily carry out sophisticated tasks for users.

Following up with a TED Talk in 2009, Tim-Berners Lee said that it’s not just about metadata, but the relationships between data:

Data is relationships. It’s got: this person was born in Berlin, Berlin is in Germany. And when it has relationships, whenever it expresses a relationship, then the other thing that it’s related to is given one of those names that starts

http. So I can go ahead and look that thing up.

Data about the content in web pages is not a big stretch from today’s web. It’s tangible because we can all see that content in our web browser. The relationships between data, thinking about how a machine would crawl through linked data and derive meaning from it, seems farther removed from what we need to build for the web.

More recently there has been a new push with support from Tim-Berners Lee to bring these ideas to social networks and new apps. The Solid spec frequently references RDF and JSON-LD.

In a FAQ for the AT Protocol, Bluesky writes about why they chose to create a new protocol instead of using ActivityPub, and why a new format instead of RDF:

RDF is intended for extremely general cases in which the systems share very little infrastructure. It’s conceptually elegant but difficult to use, often adding a lot of syntax which devs don’t understand. JSON-LD simplifies the task of consuming RDF vocabularies, but it does so by hiding the underlying concepts, not by making RDF more legible.

AT Protocol instead uses a schema system called Lexicon. It also uses JSON but is a little more concise and readable than JSON-LD. If you look at JSON responses from Mastodon, which uses JSON-LD, there is significant bloat, often with JSON-LD’s @context field taking up more space in the response than the actual content.

There are some people who have really interesting, unique needs for more complicated structured data. Those people can continue to use RDF and JSON-LD. The rest of us should use something simpler.

Let me underscore the timeline at the beginning of my story, when my friend Travis and I were giving that presentation about MCF. That was over 25 years ago. There are web developers working today that have lived their entire lives in the span of time since these ideas first started appearing.

In a post in 2001 titled Metacrap, Cory Doctorow had cut through some of the optimism:

A world of exhaustive, reliable metadata would be a utopia. It’s also a pipe-dream, founded on self-delusion, nerd hubris and hysterically inflated market opportunities.

I don’t see evidence that the Semantic Web has made much progress in those years. Maybe Solid will finally tie everything together. But the original web exploded in popularity in part because it lacked structure. It was easy to contribute to building the web because the web was so forgiving about structure.

Before we try to build a new web, let’s fix the old web first. More people should be publishing content on their own web site.

Before we try to universally categorize all data, let’s improve the metadata in the most basic of resources on the web. There’s value today in better describing data like a person’s name, their photo, when a web page was published, or the title of a blog post.

IndieWeb co-founder Tantek Çelik called this the lowercase semantic web. Smaller, less ambitious than uppercase Semantic Web, but still very useful for building apps today.

There are also semantics built into HTML 5. Elements like <time> and <section> that provide more meaning to the structure of web pages. This is plain old semantic HTML. Not glamorous, but useful and built in to web browsers.

It’s usually the simple formats that have the best chance to succeed.

Microformats provide a way to add metadata to a simple web page without creating a new format. The metadata is in the HTML itself instead of alongside it. It doesn’t attempt to be as comprehensive as RDF, and so because of its simplicity it’s lightweight enough to add directly to HTML.

It also fulfills a core IndieWeb principle to prioritize what people actually see. From the IndieWeb’s principles page:

Use & publish visible data for humans first, machines second. See also DRY.

Don’t repeat yourself. Don’t recreate all of the text that is already in the HTML, duplicating it in a separate RDF file just so that new metadata can be added to it.

Microformats actually predate IndieWebCamp by several years. You can trace it back to 2003 and the introduction of XFN, the XHTML Friends Network, by Tantek Çelik, Matt Mullenweg, and Eric Meyer. XFN used simple attributes on blogrolls — lists on your site of other blogs you liked to read — to describe your relationship to those bloggers. Each link’s rel attribute was set for whether that person was a friend, acquaintance, co-worker, or someone you had met:

<a href="https://anotherdomain.com/“ rel="met acquaintance">Someone</a>

Tools could be built to crawl sites that used XFN, creating a social graph across the web. XFN was a topic in sessions at SXSW Interactive, including a panel that described the potential scope of blog-based social networks:

…simple, user-centered technology that has turned the blogosphere into a giant decentralized social network

In 2004 at the O’Reilly Emerging Tech conference, Tantek Çelik and Kevin Marks gave a presentation where the “microformats” term was coined. One of their slides gets to the heart of the IndieWeb, that we can build what we need on simple formats in today’s web rather than invent something new:

adding semantics to today’s web rather than create a future web

Blog post dates are a good example. Adding a little extra metadata doesn’t change the display or complexity of the HTML, but makes a simple date machine-readable so that scripts and apps parsing the HTML can be certain about where the date appears and in what format. The displayed, human-readable version of the date can still be anything, or localized.

Consider a date in an HTML paragraph tag:

<p>Jan 2, 2017</p>

Add the Microformats dt-published class name to note that this text is the published date for the post:

<p class="dt-published">Jan 2, 2017</p>

Then add a datetime attribute to provide the date in a standard format that is easy to parse by a script or app:

<p class="dt-published" datetime="2017-01-02 10:30:00 +0000">Jan 2, 2017</p>

It can be further improved by using the time element from HTML:

<p><time class="dt-published" datetime="2017-01-02 10:30:00 +0000">Jan 2, 2017</time></p>

Extracting the text content from a page is also simpler with Microformats. Where before you might have:

<div>

<p>This is some post text.</p>

<p>More text here.</p>

</div>

With Microformats it becomes:

<div class="e-content">

<p>This is some post text.</p>

<p>More text here.</p>

</div>

This might seem unnecessary for a simple web page, but imagine the post surrounded by a sidebar, navigation, ads, footer, and other content. Marking up exactly where the real post text is using e-content makes it much easier to find the content.

We can build on this by wrapping the content with h-feed and one or more h-entry elements to make an HTML list readable like a traditional feed.

The idea behind Microformats is that you don’t need separate RSS or JSON feeds if all the information is right in the web page. Let’s say we have this list of posts:

<ul>

<li>

<span>

<p>Hello world.</p>

</span>

<a href=“…”>

<time>06 May 2017</time>

</a>

</li>

</ul>

Add class names via Microformats and it becomes:

<ul class="h-feed">

<li class="h-entry">

<span class="e-content">

<p>Hello world.</p>

</span>

<a href=“…” class="u-url">

<time class="dt-published" datetime="2017-05-06 20:50:00 +0000">06 May 2017</time>

</a>

</li>

</ul>

Now a feed reader can parse the web page directly and infer exactly what everything is. There are classes for users, profile photos, replies, bookmarks, and more.

Microformats today is technically the 2nd version of Microformats, commonly referred to as MF2. Many of the Microformats 2 classes evolved from an add-on specification to Microformats called hAtom. hAtom borrowed from the Atom feed format, applying Atom’s XML element names to HTML classes. You may still see web pages that reference these older names such as hentry (without the hyphen) and entry-content (instead of e-content).

| Microformats 1 | Microformats 2 |

|---|---|

| hfeed | h-feed |

| hentry | h-entry |

| entry-title | p-name |

| entry-content | e-content |

| published | dt-published |

| author | p-author |

The prefix used in Microformats 2 describes the type:

p-is for a plain-text property.u-is for a URL.dt-is for a date and time.e-is for when the value is all of the HTML inside an element.

Properties are added to child elements of a root element such as h-entry or h-card.

IndieWeb-compatible tools today are always built with Microformats 2 in mind, although some will also fall back to reading Microformats 1 for compatibility with older web pages.

The classes in Microformats were expanded as needed. In 2008, in-reply-to was proposed by Sarven Capadisli to indicate that a post was a reply to another post, inspired by RFC 4685, an extension for adding replies to the Atom spec.

<div class="h-entry">

<a href="..." class="u-in-reply-to">Replying to this post</a>

<div class="p-name p-content">Great post!</div>

</div>

Replies are common because our goal is to get web sites talking to each other. We cover this and the Webmention protocol in a later chapter.

Testing your Microformats

Because Microformats are interspersed in an HTML file along with content and other tags, not as a separate file with only the metadata, it can sometimes be more difficult to tell at a glance if you have all the Microformats you need. It’s helpful to have a simpler view of the structure of the Microformats, with everything else in the HTML removed.

These tools can help check the Microformats in your web pages:

- Aaron Parecki’s Pin13 includes a Microformats helper tool that takes a URL and downloads the HTML source, parsing it for Microformats.

- Monocle preview parses HTML that uses

h-feed, presenting a timeline view of what the posts will look like.

It often takes just minutes to sprinkle some Microformats classes into your web pages. Start on your home page, so that your profile information is available to other IndieWeb apps, and then add Microformats markup around your posts too. Some basic support of Microformats will be important when integrating with other IndieWeb building blocks like Webmention.

Next: Building blocks →