Leaving Twitter

“There aren’t many companies that get to this level. And there aren’t many founders that choose their company over their own ego.” — Jack Dorsey’s resignation letter

The first version of Twitter used a database server with auto-incrementing numbers to represent the ID for each record. Years later such a simple relational database would present scaling problems, but in June 2006 when I joined, this database design was just how you started building a web app. For every new record added to a table representing users in the database, the ID for that record is incremented, giving the next user a higher user ID.

Because this number is available in the Twitter API and shown in some apps, you could see when someone joined the platform. I was the 897th person to sign up on Twitter. For years I was proud of this low, 3-digit user ID. I loved Twitter and would excitedly describe the platform to people who were first hearing about it.

In 2008 in Chicago, I was at the C4 conference for Mac developers. When the conference ended I shared a cab to the airport with Alex Payne, who built the first Twitter API. I was so excited about the potential for the platform that I probably had a dozen ideas for Twitter apps. Alex and I sat at a cafe at the airport, waiting for our respective flights, and talked about the future.

I built several third-party apps for Twitter after that. Tweet Library was an iOS app for keeping an archive of your tweets and organizing tweets into collections. Tweet Marker was an API that other apps could use to sync the timeline scroll position across apps.

John Gruber wrote in 2009 that Twitter was perfect for experimenting with new apps:

There are several factors that make Twitter a nearly ideal playground for UI design. The obvious ones are the growing popularity of the service itself and the relatively small scope of a Twitter client. Twitter is such a simple service overall, but look at a few screenshots of these apps, especially the recent ones, and you will see some very different UI designs, not only in terms of visual style but in terms of layout, structure, and flow.

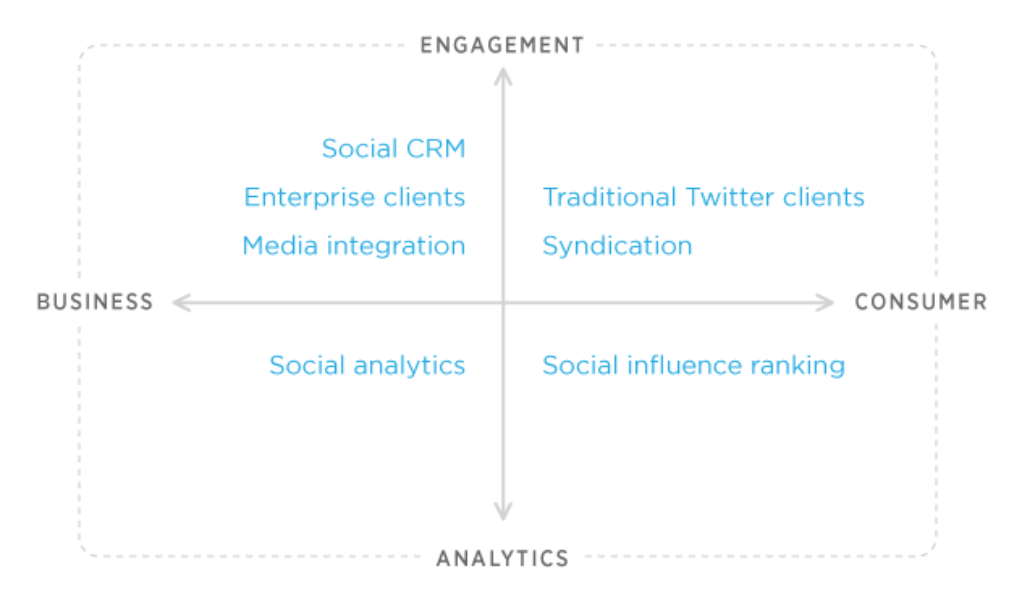

When I announced Tweet Marker in 2012, there was a vibrant Twitter developer ecosystem. It was about to erode. Just a couple months later, Twitter announced their infamous 4-quadrant chart, discouraging certain types of Twitter apps.

In one corner of the chart were the apps Twitter wanted to see: business and analytics apps. In another corner were the apps they didn’t care about: traditional clients, often the primary interface that people used to access Twitter on iOS and Android . Twitter blogged:

That upper-right quadrant also includes, of course, “traditional” Twitter clients like Tweetbot and Echofon. Nearly eighteen months ago, we gave developers guidance that they should not build client apps that mimic or reproduce the mainstream Twitter consumer client experience. And to reiterate what I wrote in my last post, that guidance continues to apply today.

Twitter was also limiting the number of auth tokens an app could have:

Additionally, if you are building a Twitter client application that is accessing the home timeline, account settings or direct messages API endpoints (typically used by traditional client applications) or are using our User Streams product, you will need our permission if your application will require more than 100,000 individual user tokens.

In 2009, before Twitter had their own official Twitter app, developer Buzz Andersen and designer Neven Mrgan shipped an early third-party Twitter app, Birdfeed. Buzz was actively working on Birdfeed through Twitter’s transition of their API from simple password-based authentication to OAuth, which required apps to register with Twitter.

Buzz said in a tweet:

Twitter isn’t just enforcing OAuth for technical reasons: it’s a way of taking control of the platform.

Removing RSS feeds followed the same playbook. There used to be RSS feeds from Twitter for reading a user’s timeline. Without feeds and without open access to the API, Twitter could make the official apps the prominent way to use Twitter, driving up engagement and ad revenue.

An email from Ryan Sarver showed part of how Twitter was changing as a company, refocusing from building a network to selling a product. Reading between the lines, it seems that to effectively sell ads, Twitter felt they needed to control the user experience. On Twitter clients:

Developers have told us that they’d like more guidance from us about the best opportunities to build on Twitter. More specifically, developers ask us if they should build client apps that mimic or reproduce the mainstream Twitter consumer client experience. The answer is no.

Then over the weekend, Ryan clarified: “we are saying it’s not a good business to be in but we aren’t shutting them off or telling devs they can’t build them.”

IFTTT — If This, Then That — was a popular way to connect different platforms together, and it depended on open APIs. IFTTT was a useful tool that helped people do more with Twitter, even if they weren’t developers. Turning off IFTTT support was the last straw for me personally because the decision seemed to encapsulate everything that was wrong about Twitter’s direction.

Matthew Panzarino wrote at The Next Web about how IFTTT removal was a “red alert” to developers:

This means that many third-party developers who thought that their complimentary services, which did not duplicate the features or feel of clients at all, were safe under the new rules will have to take a very hard look at their apps.

I had become disillusioned by this developer-hostile attitude, where third-party apps were supported only if they fit within Twitter’s business model. App.net promised a better vision, but faded away. I experimented with posting short posts on my own blog where they could outlast any silo.

The more I posted to my blog, the more regret I had about all those years giving Twitter power over my own content. As Marco Arment wrote in 2014:

Twitter started out as a developer-friendly company, then they became a developer-hostile company, and now they’re trying to be a developer-friendly company again. If I had to pick a company to have absolute power over something very important, Twitter wouldn’t be very high on the list.

Meanwhile, Twitter had gone mainstream. Alex Payne had left the company and Twitter was much different from a business and leadership perspective by the time the rest of the world started paying attention. Thousands of employees worked at Twitter. How many of them had experienced the early days of following friends’ tweets via SMS, when the service seemed genuinely new and important? The future had arrived but it was full of hashtags.

The unique tragedy with Twitter’s changing attitude toward developers is that so many of Twitter’s early innovations did come from third-party developers. The word tweet, the first use of a bird icon, and even the character counter started in Twitterrific. Twitter’s new leadership displayed an incredible disrespect for the value developers added to both the ecosystem and core platform.

So I stopped posting to Twitter in 2012. It was many things. The limits on user auth tokens, which had already killed a few popular third-party Twitter apps; the problems with shutting down IFTTT recipes; the guidelines that restricted how you could use your own tweets.

I knew leaving would be difficult, so I set up a series of posts to discourage my future self from ever joining again. My final tweets were timed to go out on the anniversary of Steve Jobs’s death. They’re a collected moment, a tribute to both Steve and how great Twitter could be. I like that they’re forever pinned at the top of my profile page.

Years later, when others would leave Twitter because of the chaos caused by Elon Musk’s acquisition, and finally his decision to shut down third-party Twitter apps, some people would tweet their final goodbyes capturing all of that rage and frustration. My last tweet wasn’t like that. It was both a goodbye and a memory of what had made Twitter special. I wanted to highlight the good parts of Twitter because there were so many people causing trouble on the platform. For every beautiful tweet, there was hate and harassment and negative tweets and sarcasm and snark.

Overlapping the developer-hostile attitude was a growing realization that Twitter was overwhelmed with managing the community. Hate and harassment spread mostly unchecked. Something about the short, 140-character posts seemed to bring out the worst in people. (I’ll cover community and replies in more detail in part 5.)

And then in 2018, the evolution of the Twitter API away from traditional client developers started becoming more real. In a blog post announcing the change, Twitter outlined how they would retire older APIs, moving to new APIs with a different pricing structure that made little sense for traditional Twitter clients:

We built a migration guide to assist in the transition from Site Streams and User Streams to the Account Activity API. As a few developers have noticed, there’s no streaming connection capability or home timeline data, which are only used by a small amount of developers (roughly 1% of monthly active apps). As we retire aging APIs, we have no plans to add these capabilities to Account Activity API or create a new streaming service for related use cases. Home timeline information remains accessible for developers via the statuses/home_timeline endpoint.

With the API more limited, there was less incentive to build fun tools that worked with Twitter. Tim Haines wrote about how Twitter deprecating the streaming API led him to shut down his service Favstar:

Twitter wrote that they’ll be replacing this with another method of data access, but have not been forthcoming with the details or pricing. Favstar can’t continue to operate in this environment of uncertainty.

It had taken nearly 6 years, but it felt like 2018’s API changes finally wrapped up the work that started in 2012. The apps that are possible with the new Account Activity API are exactly the apps that were encouraged in those other quadrants. The pricing made no sense because it wasn’t designed for traditional Twitter apps like Twitterrific and Tweetbot.

Twitter’s history has been tumultuous. Jack Dorsey as CEO was out, then back in. The API was open, then closed, then more open again. And all through it, Twitter’s features hadn’t changed much until recently.

Then in 2022, Elon Musk bought Twitter. Massive layouts followed, leaving very few people to manage the API. There was a series of mishandled feature rollouts. Native third-party apps were completely cut off from the Twitter API, and even basic API access was moved to paid plans.

Dave Winer blogged about the Twitter API changes:

Corporate platforms always fail, given enough time. The Twitter API had a good run. Now the deck is clear, and there’s room to make some new stuff, or just take a break and smell the roses a bit, or go for a bike ride. 🤪

In the long run, the open web will be better off without Twitter. There is renewed interest in decentralization.

Many people blamed Elon Musk, and it became a convenient narrative to assign any failure to his leadership. The problems had started much earlier, though. Ben Thompson discussed this on the Sharp Tech podcast:

Part of the irony of everyone getting upset about Elon Musk killing all the third-party Twitter apps is that that’s what Twitter’s management should have done a decade ago. If you’re going to go in that direction, go in that direction. Instead they didn’t have the guts to sort of follow through in their strategic decision to its logical endpoint.

I stopped posting to Twitter in 2012 exactly because of this strategy. Elon had greatly accelerated what was already the path for Twitter fading into silo irrelevance. I wish I could come up with a less violent analogy, but what comes to mind is Twitter leadership in 2012 loading the gun and pointing it at third-party apps, but it wasn’t until 2023 that anyone pulled the trigger.

Elon deservedly gets most of the blame for Twitter’s recent chaos. But Twitter wasn’t going to last forever under any version of its clown car leadership over the last decade. In the long run, we will be thankful that Elon is effectively putting the company out of its misery. We’re going to see innovation on the open web as third-party developers realize they are the ones who have actually been given new life.

And people are realizing that as unimaginable as it first seemed to not use Twitter, once you cut it out of your life it’s fine. Other networks like Mastodon and Threads take its place, or private chats with friends, or other hobbies. Robin Sloan captured this beautifully:

The speed with which Twitter recedes in your mind will shock you. Like a demon from a folktale, the kind that only gains power when you invite it into your home, the platform melts like mist when that invitation is rescinded.

Even the name itself and the bird branding are gone. The letter X feels like an appropriate placeholder for the platform’s grave. Here lies a dying platform. X marks the spot where it used to be.

The Twitter founders had stumbled onto something world-changing. The momentum of a unique idea carried them for years, even flawed, even as they lost their way. For indie microblogging to succeed, we must be more thoughtful and deliberate about the future.

Next: App.net →