Webmention

“The internet does not need a conversation layer. It is the conversation layer.” — Derek Powazek

Webmention is a W3C recommendation that enables cross-site replies. You can write a blog post on your own site, at your own domain name, and I can reply to that post on my own site.

I don’t need to write a separate comment on your site. Instead, my site notifies your site about my reply via Webmention. Your site can then choose to automatically include my reply on the same page as your post, as if my reply was a traditional blog comment.

By writing replies on our own web sites, we can control the URLs and better own our content. Conversations can be distributed across the web instead of needing to be contained together at a silo.

Webmention is useful even if you don’t want your replies to be displayed next to your regular blog posts. Micro.blog currently stores replies separately, but it still uses Webmention when replying to external blogs so that the reply can be included along with the original post.

Chris Aldrich wrote in an article for A List Apart about how powerful a concept Webmention is:

Webmentions help to break down some of the artificial walls being built within the internet and so help create a more open and decentralized web.

Even without Webmention, the web of course is linked with <a> tags, one blog post linking to another. While you could look at log files or JavaScript-based analytics and see who is linking to your blog, what’s missing with a regular link is any indication of why the link exists. Is the blog post a reply to another post, or referencing it for other reasons?

TrackBack was an early specification that attempted to make this link more explicit. TrackBack was created in 2002 by Six Apart for Movable Type, and then supported in several other blogging platforms. It supported notifying — or “pinging” — a blog that you were linking to:

The ping provides a firm, explicit link between his entry and yours, as opposed to an implicit link (like a referrer log) that depends upon outside action (someone clicking on the link).

To use TrackBack, web sites needed to include a snippet of RDF in their pages for discovery. The ping itself was sent as form-encoded parameters. At a minimum, the URL of the reply would be included, with optional parameters for title or blog post excerpt.

Pingback was introduced by Stuart Langridge as an “automatic TrackBack” that would look at your post for links and ping those blog posts using XML-RPC:

Just go ahead and blog as you normally do, and it’ll all happen automatically. It doesn’t have to happen with XML-RPC, it could just be a page request. My thinking there was that RPC makes it easy to generalise, and most blogging systems incorporate XML-RPC libraries now anyway, to support remote blogging tools.

Pings were still sent via XML-RPC, but Pingback improved discovery by using a <link> tag instead of embedding more verbose RDF in the web page.

Webmention evolved from TrackBack and Pingback, improving upon those early formats in a few key ways:

- Keeping the simpler discover method from Pingback.

- Simple HTTP POSTs instead of XML-RPC.

- Didn’t include the title or excerpt of the post, which could be used to add spam comments to a blog post, and which didn’t look very good anyway.

In a reply on his blog years later, Aaron Parecki outlined why Pingback had been a poor user experience for blog comments:

Pingback never went far enough with the user experience of displaying them. At best, you’d see a snippet of the text near the link, which it turns out wasn’t really that useful or contextual. Once social media started taking off, the interactions there became far richer than seeing the pingback excerpt, so people abandoned them.

Instead of using those short excerpts of a comment, Webmention builds on Microformats to let the full reply text appear on the blog post, including any formatting used in the reply. The blog receiving the reply makes a request back to the blog post that is sending the reply, downloading the HTML with Microformats for the post.

Having the HTML of the reply means we can check that it actually links to the blog post that is being replied to. This will help avoid spam comments. And by using Microformats, we can find exactly which text should appear as a comment on the receiving blog.

How Webmention works

The first step to sending a Webmention is discovering the endpoint URL to send the web request to. On the blog’s web page for which you’re sending a Webmention, check the HTML source for a link tag with rel="webmention". This is similar to looking up a Micropub API endpoint.

<link rel="webmention" href="https://micro.blog/webmention">

All Micro.blog-hosted blogs use the same Webmention endpoint URL. External blogs such as WordPress will use a URL provided by the Webmention plugin for WordPress.

Webmentions are sent to the endpoint URL as an HTTP POST with essentially just two form-encoded parameters:

source: the URL of the new replytarget: the URL of the original post being replied to

Here’s an example:

POST /webmention

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

source=https://micro.blog/manton/7902528&target=https://anotherdomain.com/original-post

Like Micropub, Webmention is simple enough that it can even be sent with the curl command line tool:

curl -d "source=https://micro.blog/manton/7902528" -d "target=https://anotherdomain.com/original-post" "https://yourdomain.com/webmention"

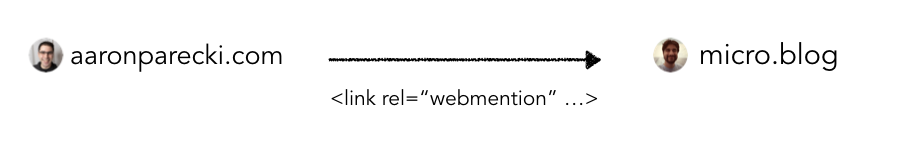

To illustrate this flow, imagine Aaron Parecki is posting to his blog. I see the post in Micro.blog and reply to it. Micro.blog should first discover Aaron’s Webmention endpoint by downloading the HTML for the target blog post:

Aaron’s blog will return the HTML, including the link tag:

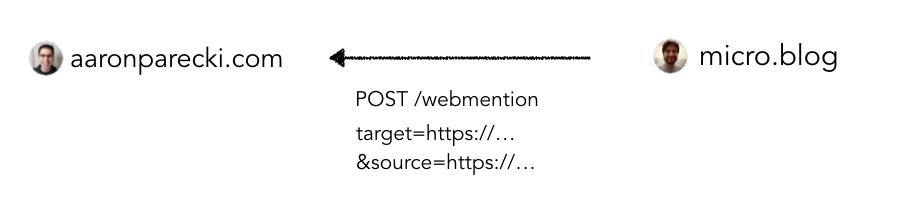

Now that Micro.blog has the Webmention endpoint, it can ping it with the source and target URL parameters:

When receiving the Webmention, Aaron’s blog will download the reply from Micro.blog and look for the Microformats post content. Aaron’s blog can then add my reply on his blog post.

Usually software like Micro.blog will handle this automatically. If you need to manually send a Webmention, the web-based tool Telegraph includes a convenient Send a Webmention feature. It will discover the Webmention endpoint URL for you based on the post you are sending a reply to.

In Micro.blog, you can @-mention another web site even if that user does not have a Micro.blog account. Starting a post with @yourdomain.com will send a Webmention to the target web site’s home page. Likewise, external web sites can send Webmentions to blog posts that appear on Micro.blog.

Sending replies manually

When you use Micro.blog’s built-in reply feature, Micro.blog handles sending the Webmention for you. But what if you want to reply to someone’s blog post that isn’t included in the Micro.blog timeline already, so there is no reply link?

To construct a reply, use Microformats u-in-reply-to with an HTML link:

Great post <a href="..." class="u-in-reply-to">on this blog</a>. Really enjoyed it.

When Micro.blog sees your post, it will automatically notice the u-in-reply-to class and send a Webmention for you, handling all the discovery for the external blog.

If you’re not using Micro.blog, the HTML will be the same, but you’ll want to have another process to discover the Webmention endpoint and send the ping.

WordPress comments

By installing the Webmention plugin for WordPress, Webmention pings from other sites will appear as WordPress comments. This includes replies from Micro.blog.

Here’s how the flow of replies to WordPress work:

- You publish a new blog post to your WordPress site.

- The post shows up in the Micro.blog timeline.

- Another user sees the post in Micro.blog and replies to it.

- Micro.blog sees that the reply is to an original post on the web and checks that post for whether your site supports Webmention.

- Micro.blog sends a Webmention to your site, passing the source URL for the conversation on Micro.blog that contains the new reply.

- WordPress accepts the Webmention and adds a new comment on your post.

That reply is marked up with Microformats automatically by Micro.blog. This markup includes the author’s name, profile photo, and the actual reply text. By adding this extra data to the reply web page, WordPress can parse the page and extract the details it needs to show the comment on your site.

Here’s an example of what the markup looks like on a Micro.blog reply.

<div class="h-entry">

<a href="..." class="u-in-reply-to">In reply to</a>

<div class="p-author h-card">

<a href="/manton" class="u-url">

<img src="..." class="u-photo" width="48" height="48" alt="manton" />

</a>

</div>

<div class="e-content p-name">

<p><a href="https://micro.blog/manton">@username</a> This is the reply text.</p>

</div>

<a href="..." class="u-url"><time class="dt-published" datetime="2020-01-21T21:49:09+00:00">3:49 pm</time></a>

</div>

I’ve simplified the HTML to remove some of the Micro.blog-specific layout, focusing on just the important Microformats:

h-entry: wraps all of the content for this reply.u-in-reply-to: the URL that this reply is replying to.p-author,h-card, andu-photo: the profile photo for who is sending the reply.e-content: the actual reply text.dt-published: the time the reply was sent.

Because this system is based on Webmention, it doesn’t just work with Micro.blog. Any blog can post a reply to a WordPress blog and have that post show up as a comment in WordPress.

To make sure these comments include the data from Microformats, install the Semantic Linkbacks plugin for WordPress.

Combined with Micro.blog’s ability to follow IndieWeb-friendly blogs by using their domain name for the username, like @yourdomain.com, it’s possible for WordPress bloggers to participate in Micro.blog and get replies from Micro.blog users without ever creating an account on Micro.blog itself.

Webmention on static sites

Static-site generators like Jekyll and Hugo can’t accept dynamic requests like Webmention pings. There is no database on a static server to keep track of incoming data. To support Webmention, static sites should use an external service like Webmention.io to handle receiving the replies.

Add a link tag to point to webmention.io. When you register on Webmention.io, you’ll have a username which you can use in the endpoint URL:

<link rel="webmention" href="https://webmention.io/username/webmention">

Now when someone replies to your blog posts, the Webmention ping will be sent to Webmention.io. Webmention.io will record it in its database, making the data available via an API or from JavaScript.

Another project, Webmention.js, builds on Webmention.io to make it easier to show replies for a blog post without writing JavaScript yourself.

It’s even possible to replace Micro.blog’s own Webmention endpoint with Webmention.io, if you want to keep track of replies and display them in a different way. Micro.blog user Steve Layton has written a blog post about how to use a custom Micro.blog theme to do this.

Micro.blog has built-in support for Webmention, including retrieving replies for a specific post. You can use Conversation.js to automatically include replies on your blog post page.

Conversation.js is a snippet of JavaScript you can paste into any blog theme. Wherever you use this JavaScript, Micro.blog will insert the replies for that post. Here we’re using Hugo’s .Permalink to pass the current blog post URL:

<script type="text/javascript" src="https://micro.blog/conversation.js?url={{ .Permalink }}></script>

Or if you’re building your own solution, you can retrieve replies via Micro.blog’s API like this:

GET /webmention?target=https://my-blog-post&format=jsonfeed

Host: micro.blog

If you use format=jf2, the response will be in the same format returned by Webmention.io. This kind of consistency makes it easier to switch between Webmention providers. It’s another value of the modularity of IndieWeb building blocks.

RSVPs

Webmention can be used for more than just traditional replies. By adding a little extra HTML to your post, you can send a Webmention for special cases, such as RSVP-ing to an event.

Like a reply to a blog post, an RSVP should link to the event with the Microformats u-in-reply-to. An RSVP is essentially a reply to an event. We also need to include a value with p-rsvp for whether we will be attending.

<span class="p-rsvp">Yes</span>, I’ll be attending <a href="https://events.indieweb.org/2020/06/indiewebcamp-west-2020-ZB8zoAAu6sdN" class="u-in-reply-to">IndieWebCamp West</a> later this month.

RSVPs can have one of the following values:

- yes

- no

- maybe

- interested

We can also include this value outside of the text in our blog post by using the data HTML tag. A web browser won’t show this, but the receiving endpoint that is processing the Webmention can still record our answer:

<data class="p-rsvp" value="yes" /> I'll be attending <a href="https://events.indieweb.org/2020/06/indiewebcamp-west-2020-ZB8zoAAu6sdN" class="u-in-reply-to">IndieWebCamp West</a> later this month.

For short microblog posts, the web site receiving the Webmention can use the text of your post to display with your RSVP. For longer blog posts, you may want to provide a shorter RSVP message that is not included in the full post, so that the event web site can show only the short RSVP, and not your full blog post, which might need to be truncated. This also uses the data HTML element:

<data class="p-rsvp" value="yes">I’ll be attending this event.</data>

Because not all blog post templates contain author information with the post, it sometimes might be helpful to add your name and profile photo directly to the post. Then the site receiving the RSVP can display it.

To add a hidden name and profile photo to the post, use a style with display: none so that web browsers don’t show the profile photo. You can also use a data element, similar to what we used above for the p-rsvp itself, to include your name without displaying it on your blog post:

<a class="p-author h-card" href="https://manton.org/" style="display: none;"><img src="https://micro.blog/manton/avatar.jpg" class="u-photo" /><data class="p-name" value="Manton Reece" /></a>

This is a little bit of a hack, though, and not all event sites that receive the RSVP will respect the display: none style. Even better is to make sure that your blog theme has an h-card with the profile photo on every page.

After you’ve created your RSVP blog post, the final step is to notify the event’s web page by sending it a Webmention:

POST /webmention

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

source=https://yourdomain.com/rsvp/...&target=https://events.indieweb.org/…

Webmention is a simple protocol that on its own may appear to do very little. Combined with Microformats and platforms that can store and display reply data, though, it provides the infrastructure for cross-site replies and a flexible set of other reactions like RSVPs and likes, giving our independent blogs the functionality of a social network built for the whole web.

To make this easier for Micro.blog, I created a plug-in called IndieRSVP that adds a Hugo rsvp shortcode that you can use in your blog posts. It takes the event URL and adds the u-in-reply-to and p-rsvp for you:

I'm going to this! {{< rsvp href="https://events.indieweb.org/2022/03/micro-camp-2022-IW2Qp3ygHike" >}}

Micro.blog will notice the link and automatically send the Webmention for you. We noticed more RSVPs being sent to Micro Camp 2022 as soon as this was a little easier with the plug-in.

Looking back on the 2002 book Small Pieces Loosely Joined, David Weinberger reminds us that the web was not intended to be an application platform. It’s about documents and parts of documents.

A centralized platform like Facebook or LinkedIn does not need to concern itself as much with replies across web sites. It’s all about keeping the content and discussion on a single web site.

For a more distributed web, with replies spread across different sites, a protocol like Webmention is needed to connect conversations together. And when more indie blogs support Webmention, it also enables bridging tools between social networks and blogs.

Next: Bridgy →