Permanence

“I cannot imagine the future, but I care about it. I know I am a part of a story that starts long before I can remember and continues long beyond when anyone will remember me.” — Danny Hillis, The Long Now Foundation

The sun never set on July 8, 2020 in Svalbard. Every day in the summer the sun shines on glaciers across the archipelago. Underground, an abandoned coal mine has been repurposed as a storage vault, a remnant of Svalbard’s past as a mining community. It was cold outside at the old mine when trucks arrived carrying boxes from GitHub because it’s always cold, 800 miles inside the arctic circle.

Later in the winter, the northern lights will paint across the sky. Time feels like it slows down, as the days and nights extend for seasons. It’s a fitting environment for archiving code that will last for generations.

Part of the GitHub Archive Program, the GitHub Arctic Code Vault project takes a snapshot of GitHub and stores it in that climate-controlled storage underground in Svalbard. Thousands of repositories from GitHub are encoded on reels of film, like old newspapers on microfilm at a library. In this format and in this environment, it’s estimated that the code can be preserved for 1000 years.

These great lengths were taken with an offline archive because sometimes it seems that nothing lasts on the internet. I could write on my blog for years and the next day get hit by a bus. Without some care and planning, the domain expires, the posts are lost, and it doesn’t matter if I had 10 readers or 10,000. To the internet, it’s as if it never happened.

The GitHub archive attempted to solve this fragility by making physical copies on those reels of film. No specific computer is necessary to review the code. It can be read with no greater technology than a microscope.

It’s like the difference between a physical book compared to an e-book. There is something durable about a simple, cheap book on a bookshelf. One day in our house I found a paperback of an old favorite, Tigana, which I had bought while traveling in Europe. Inside the cover I had written “Oxford, 1999”. I flipped through the pages and out fell a wine label that I hadn’t seen in over a decade. It was from a bottle of wine my wife and I had in Greece, sitting on the sand of an island beach the night I proposed.

I had kept it back then because I knew years later it would matter — a memory fused into a piece of paper, waiting. That trip was a story told in events like that one, in personal journals, and through email to family. The digital parts of the story didn’t last. The email was purged by Yahoo! Mail during their regular server housecleaning.

Write on Twitter and it mostly vanishes from the internet after thousands of new tweets have pushed it away, unlinked and undiscoverable. But write the same on a scrap of paper tucked into a book and it will be rediscovered again years later.

A self-published novel in PDF on your web site is a ticking time bomb, waiting for your hosting bill to go unpaid. But print 10 copies and give it to 10 friends and it lasts forever.

Patrick Rhone in his Micro Camp 2021 talk compared paper copies to backing up digitally. If you want something to last 1000s of years, paper is better:

If you really want to back up your blog — and make it durable, make it something that will last, make it something that maybe your grandchildren or great grandchildren might read — the best way to do that is to print it out.

The only way to preserve something is to make multiple copies and distribute them. The problem with digital media is that it makes it just as easy to accidentally delete or lose copies as it is to create them. Evolving file formats and storage devices require constant supervision and maintenance, pushing files up each technology bump from floppy disks to CDs to DVDs to hard drives to the cloud. It never ends.

Adrienne LaFrance wrote a story for The Atlantic about lost content on the web, including a Pulitzer Prize-nominated web series that vanished:

The promise of the web is that Alexandria’s library might be resurrected for the modern world. But today’s great library is being destroyed even as it is being built. Until you lose something big on the Internet, something truly valuable, this paradox can be difficult to understand.

Bloggers will keep running into this until we take steps to solve it. It’s something Dave Winer has written about, calling the topic “future-safe archives”. It’s something anyone with a large collection of writing online probably thinks about. How do we preserve the culture and art and stories of our time when the preferred media are so fragile?

One answer is control. By publishing to our own web site, it’s up to us where the posts and replies are copied to, mirrored, and how long they last.

The IndieWeb wiki has a page dedicated to site deaths: centralized content silos that have shut down and taken our content with them. When we cede control to a silo, especially one whose priorities don’t match our own, it becomes more difficult to make copies of our data, or move our posts later without breaking links to them from elsewhere on the web.

If someone isn’t maintaining their blog, maybe they don’t notice if their domain name or hosting account accidentally expires. If someone isn’t posting to a silo anymore, maybe they don’t see the notification that it’s shutting down and taking their content with it.

Elena Cresci wrote a post for Medium’s OneZero about silos purging content, talking to bloggers who had lost important content:

What do we lose when huge parts of what used to be central to our online experience are wiped out? Embarrassing Myspace photos aside, we lose crucial historical context to how we lived our lives online — which is why a number of institutions and groups have arisen to try to archive the web.

As awareness grows about this problem, more and more people have stepped up to help. There are many developers who are quietly extending the life of web content.

The team at the Internet Archive has fixed 9 million broken links on Wikipedia by scanning pages for broken links and updating them to point to the Wayback Machine’s copy:

And for the past 3 years, we have been running a software robot called IABot on 22 Wikipedia language editions looking for broken links (URLs that return a ‘404’, or ‘Page Not Found’). When broken links are discovered, IABot searches for archives in the Wayback Machine and other web archives to replace them with.

Mirroring content to other platforms so that it can be preserved isn’t a new idea. The Wayback Machine at the Internet Archive launched in 2001.

Interviewed by Jason Calacanis in 2020, Internet Archive founder Brewster Kahle reflected on the mission of the Internet Archive:

The idea of the Internet Archive is to build universal access to all knowledge. Can we make it so that anybody curious enough that wants to have access to anything ever published. A book, or a lecture that was made available, or old web pages. Can we make it so that people could go and learn from it and build on it, and then build new things that are worthy of sharing.

Kayle also emphasized that we need multiple copies of something. Usually there is only one copy, at a publisher’s web site, and Kahle said that “1” is “almost always the wrong answer”.

We need more platforms that can offer mirroring outside the Internet Archive too, and that’s what Micro.blog has tried to do. We have a GitHub archiving feature that takes your blog posts and photos and copies them to a GitHub repository. That way they can be served by GitHub, or downloaded and backed up.

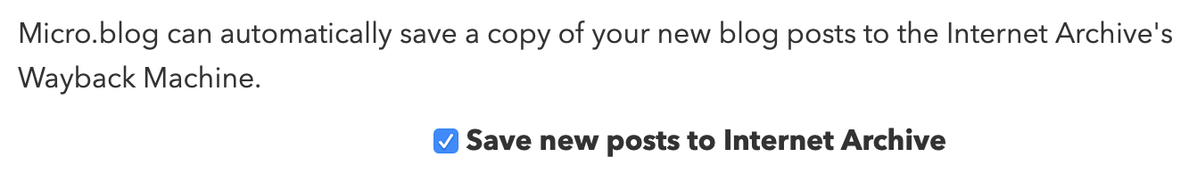

Micro.blog also has a checkbox to enable saving posts to the Internet Archive whenever you post them. It doesn’t require any technical knowledge or configuration. It’s just a checkbox that anyone can use.

And finally, Micro.blog itself can archive the contents of web pages that are bookmarked. It downloads the web page, including any linked images or CSS, and stores them on Amazon’s S3 as public links, like a miniature, personalized Wayback Machine.

There are a few simple things you can do to make your blog easier to archive and mirror:

- Use simple HTML, with separate pages for every blog post.

- Avoid features that require JavaScript.

- Limit external dependencies. Serve your photos and other media from the same domain name as your HTML, so that everything can be moved together.

Jeff Huang also has a collection of good tips on making a web page last, starting with that first point of using simple HTML that is easily portable to any web host:

I think we’ve reached the point where html/css is more powerful, and nicer to use than ever before. Instead of starting with a giant template filled with .js includes, it’s now okay to just write plain HTML from scratch again.

Permanence on the web is more than the technical side of how to keep our content online. It’s also the care we put into it. The willingness to keep typing and click “post”, year after year.

Brent Simmons wrote, as he marked the 20th anniversary of his blog:

It’s tempting to think that The Thing of my career has been NetNewsWire. And that’s kinda true. But the thing I’ve done the longest, love the most, and am most proud of is this blog.

The great thing about a personal blog is that if you stick with it, your blog will very likely span multiple jobs and even major life changes. You don’t need to know where you’re going to be in 20 years to start a blog today and post to it regularly. Writing about the journey — and looking back on the posts later to reflect on where you’ve been — is part of why blogging is still so special.

One of the reasons to own your content is to make it last. When you have control of the text you write or the photos you post, it’s up to you whether that content stays on the internet. When you post to someone else’s platform, you’ve given up that control. It’s not up to you whether the company that hosts your content will stay in business or change everything to break your content.

If we want to write something that will last, even if it’s short, we have to think in years and decades. We don’t need to bury our blog in an abandoned coal mine near the arctic circle, but we do need to be deliberate, making choices about hosting and formats that give us the most flexibility later. If it’s worth writing something, it’s worth owning it.

Next: Silos →