Misinformation

“We must reject the culture in which facts themselves are manipulated, and even manufactured.” — Joe Biden, January 20th, 2021

Go back to 2016. Awareness might have hinged on 77,000 votes across Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania. On the morning of November 9, 2016, the United States woke up to a president-elect Donald Trump, and the search for answers began. Trump had benefited from foreign interference and a widespread misinformation campaign, conducted through social media.

This was when many of us realized how deep the privacy issues ran in Facebook. In their attempt to become a platform for apps, Facebook had opened Pandora’s box. They’ve spent the last few years trying to close it.

Misinformation littered the Facebook news feed, fake headlines re-shared to friends over and over. Hillary Clinton, writing in her book What Happened:

Throughout the 2016 campaign, I watched how lies insinuate themselves into people’s brains if hammered often enough. Fact checking is powerless to stop it. Friends of mine who made calls or knocked on doors for me would talk to people who said they couldn’t vote for me because I had killed someone, sold drugs, and committed any number of unreported crimes, including how I handled my emails. The attacks were repeated so frequently that many people took it as an article of faith that I must have done something wrong.

Facebook, as the world’s largest platform, intertwined several problems — viral spread of fake news, information bubbles, and Cambridge Analytica’s harvesting of user data — pushing them together at scale to create a perfect storm of misinformation. Not a coordinated political campaign but digital chaos outside traditional polls and media.

Cambridge Analytica was a company that gathered the personal data Facebook originally allowed third-party apps to access, including data on friends that used an app. While only 270,000 people directly used the app, Cambridge Analytica was able to collect data on over 87 million people from those connections. They used this data to help political campaigns more efficiently target ads.

Facebook executive Andrew Bosworth, in an internal post years later that was leaked and then posted publicly, pushed back against some of the characterization in the press that Facebook should have done more to prevent misinformation on their platform. While he argued that the facts are often wrong when criticizing Facebook, the scrutiny they’ve received is “broadly right”:

The company Cambridge Analytica started by running surveys on Facebook to get information about people. It later pivoted to be an advertising company, part of our Facebook Marketing Partner program, who other companies could hire to run their ads. Their claim to fame was psychographic targeting. This was pure snake oil and we knew it; their ads performed no better than any other marketing partner (and in many cases performed worse). I personally regret letting them stay on the FMP program for that reason alone.

Cambridge Analytica also played a role in Brexit. In an article for The Guardian only months after the election, Carole Cadwalladr helped untangle the relationship between billionaire Robert Mercer, who had funneled millions of dollars to Trump, and Robert’s investment in Cambridge Analytica. Carole also talked to Andy Wigmore, communications director for Leave.eu. While leave has denied they hired Cambridge Analytica, Andy shared how Facebook was the key to their entire Brexit campaign:

A Facebook ‘like’, he said, was their most “potent weapon”. “Because using artificial intelligence, as we did, tells you all sorts of things about that individual and how to convince them with what sort of advert. And you knew there would also be other people in their network who liked what they liked, so you could spread. And then you follow them.

All of this was possible because of how much data Facebook collects: what you like, who your friends are, who your friends' friends are. But also because Facebook is a platform to serve ads. It provides both the means for who to target with what message, and a platform for targeting them.

In a later TED Talk, Carole expanded on the role of Facebook in Brexit, telling the story of how she talked to people who were worried about immigration. These people were repeating the same messaging they saw in Facebook ads. And these ads were shown in the news feed but there was no archive and no transparency into what people were seeing:

Most of us never saw these ads, because we were not the target of them. Vote Leave identified a tiny sliver of people who it identified as persuadable, and they saw them. And the only reason we are seeing these now is because Parliament forced Facebook to hand them over.

Platforms should be transparent, but ad-based platforms often have unclear rules for what any given user will see. Promoted tweets are ads that can exist only in certain user timelines, not generally available on the profile for the account that owns the promoted tweet.

Because blogs are associated with an author and their own domain name, they provide a more permanent, stable record for content. There are no tricks, hidden posts, or content targeted at a subset of users.

Ad-based networks like YouTube let advertisers give in to “the algorithm”, not knowing which videos their ads are running on. John Gruber blogged about this when it was revealed by The Guardian that 100 top brands were effectively funding climate change misinformation:

I really feel as a culture we are barely coming to grips with the power of YouTube, Facebook, and to some degree, Twitter, as means of spreading mass-market disinformation. The pre-internet era of TV, print, and radio was far from a panacea. But it just wasn’t feasible in those days for a disinformation campaign — whether from crackpots who believe the nonsense, corporate industry groups, or foreign governments — to get in front of the eyes of millions of people.

Misinformation fuels conspiracy theories. It’s a threat to democracy, if we don’t know who to trust. It’s the threat of fear, if hate leads to terrorism.

In 2019 there was a mass shooting at mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand. My heart goes out to the families of loved ones at the mosques and all of New Zealand. After an earlier shooting in Parkland, Florida, I drafted a long blog post about gun violence but never ended up posting it. Even after editing it a few times a month later, it felt like the words or timing were always wrong.

Over the last couple of years we’ve seen a growing backlash against social media. I won’t look for the video of this tragedy from New Zealand, and I hope I never accidentally see it. It is heartbreaking enough with words alone. Every story I read about it kept pointing back to the frustration with how Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube are not doing enough to prevent their platforms from amplifying misinformation and hateful messages.

Margaret Sullivan of the Washington Post writes about the problems with social media leading up to and after a tragedy like this mass shooting:

To the extent that the companies do control content, they depend on low-paid moderators or on faulty algorithms. Meanwhile, they put tremendous resources and ingenuity — including the increasing use of artificial intelligence — into their efforts to maximize clicks and advertising revenue.

Charlie Warzel of the New York Times covers this too:

It seems that the Christchurch shooter — who by his digital footprint appears to be native to the internet — understands both the platform dynamics that allow misinformation and divisive content to spread but also the way to sow discord.

Facebook said that in the 8 months after the shooting, they had taken down 4.5 million pieces of content related to it.

In an A List Apart article on how tech companies are protecting hate speech, Tatiana Mac asks who benefits from these cruel videos being shared:

The mass shooter(s) who had a message to accompany their mass murder. News outlets are thirsty for perverse clicks to garner more ad revenue. We, by way of our platforms, give agency and credence to these acts of violence, then pilfer profits from them. Tech is a money-making accomplice to these hate crimes.

Fake news and sensational videos spread quickly. Nick Heer links to an article in The Atlantic where Taylor Lorenz documents how after following a far-right account, Instagram started recommending conspiracy accounts to follow, which filled her feed with photos from Christchurch:

Given the velocity of the recommendation algorithm, the power of hashtagging, and the nature of the posts, it’s easy to see how Instagram can serve as an entry point into the internet’s darkest corners. Instagram “memes pages and humor is a really effective way to introduce people to extremist content,” says Becca Lewis, a doctoral student at Stanford and a research affiliate at the Data and Society Research Institute.

After the shooting, there was an outpouring of support on social media and personal sites. Duncan Davidson asked on his blog: “What are we going to do about this?”

The last few years, the worst side of humanity has been winning in a big way, and while there’s nothing new about white supremacy, fascism, violence, or hate, we’re seeing how those old human reflexes have adapted to the tools that we’ve built in and for our online world.

I can’t help but think about Micro.blog’s role on the web whenever major social media issues are discussed. We feel powerless against world events because they’re on a scale much bigger than we are, but it helps to focus on the small things we can do to make a difference.

Micro.blog doesn’t make it particularly easy to discover new users, and posts don’t spread virally. While some might view this as a weakness, and it does mean we grow more slowly than other social networks, this is by design. No retweets, no trending hashtags, no unlimited global search, and no algorithmic recommended users.

We are a very small team and we’re not going to get everything right, but I’m convinced that this design is the best for Micro.blog. We’ve seen Facebook’s “move fast and break things” already. It’s time for platforms to slow down, actively curate, and limit features that will spread hate.

It’s okay to be wrong on the internet. As long as it’s within the law and not hurting anyone. As long as it’s not amplified to a larger audience.

If everything is a social network with trends and algorithms, there would be no place to be wrong because being wrong on social risks spreading misinformation. We need quieter spaces too, corners of the internet where there’s just a simple web page with bad ideas that no one links to.

Perhaps we lose something when everything is moderated at the same level. When everything is sanitized and politically correct.

This is at the heart of Micro.blog’s effort to combine both blog hosting and a social timeline. Each half of the platform has its own purpose and its own requirements for moderation. On the social side, there’s less tolerance for being a jerk or harassing others. On the open web hosting side, there’s more freedom to yell into the void.

Instagram is not immune to misinformation. In June 2019, an Instagram account named “Sudan Meal Project” promised to give a meal to starving Sudanese children when the account was followed or shared. It amassed hundreds of thousands of followers before everyone realized it was fake.

Taylor Lorenz wrote for The Atlantic about dozens of similar fake accounts, all making promises they can’t keep and spreading “facts” about Sudan that were not even accurate:

When tragedy breaks out, it’s natural to turn to social media to find ways to help. But legitimate aid organizations—most of which don’t have the social-media prowess of top Instagram growth hackers—are no match for the thousands of Instagram scammers, meme-account administrators, and influencers who hop on trends and compete for attention on one of the world’s largest social networks.

All it takes is one person to search and find the fake account, repost it, like it, and as if it’s a snowball rolling downhill, it gathers more likes and links and eventually seems like a legitimate account. Big social networks like Instagram are designed to amplify accounts that gain traction, whether they are fake or not.

Micro.blog limits search and avoids public likes and reposts so that the snowball starts small and stays small. Instead of going viral and becoming a major problem, fake accounts can be spotted early and shut down if necessary.

Fringe views are amplified by repetition. In an investigation by The Verge about Facebook content moderators, they discovered that the moderators who kept viewing the same misinformation over and over started to believe the lies they were hired to moderate:

The moderators told me it’s a place where the conspiracy videos and memes that they see each day gradually lead them to embrace fringe views. One auditor walks the floor promoting the idea that the Earth is flat. A former employee told me he has begun to question certain aspects of the Holocaust.

In 2019, Twitter announced in a blog post that they have removed over 900 fake accounts spreading misinformation about the protests in Hong Kong:

This disclosure consists of 936 accounts originating from within the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Overall, these accounts were deliberately and specifically attempting to sow political discord in Hong Kong, including undermining the legitimacy and political positions of the protest movement on the ground. Based on our intensive investigations, we have reliable evidence to support that this is a coordinated state-backed operation.

I like that Twitter is being proactive and transparent about this. It’s especially remarkable that they notified a competitor, Facebook, about similar fake accounts on Facebook’s platform.

Unfortunately there’s a deeper problem here. It’s not just the fake accounts and misinformation, but the way that Twitter’s design can be exploited. It is too easy to piggyback on trending hashtags to gain exposure.

Maciej Cegłowski of Pinboard called attention to the promoted tweets:

Every day I go out and see stuff with my own eyes, and then I go to report it on Twitter and see promoted tweets saying the opposite of what I saw. Twitter is taking money from Chinese propaganda outfits and running these promoted tweets against the top Hong Kong protest hashtags

I wrote about this in 2018 when introducing Micro.blog’s emoji feature:

Hashtags and Twitter trends go together. They can be a powerful way to organize people and topics together across followers. But they can also be gamed, with troublemakers using popular hashtags to hijack your search results for their own promotion or unrelated ranting.

We’ve expanded search and discovery in Micro.blog slowly for this reason. While Micro.blog is certainly too small to attract the attention of state-run propaganda, there has been spam going through Micro.blog that no one else sees. We have disabled thousands of accounts. Limited search, no trends, and active curation are the right foundation so we don’t end up with a design that creates problems when Micro.blog does get bigger.

We need to minimize the points where platforms can be exploited. Indie microblogging puts the focus back on people and their identity on the web, making what you see in your timeline a more deliberate act.

Avaaz is a network for activists that covers a range of issues, including a report about fake news on Facebook ahead of the 2020 election. They think social platforms can go even further to “correct the record” when fake news has tricked users into believing lies. Because fake news often spreads virally and much farther than the correction, it’s important to notify users who have viewed fake news that there is a correction:

This solution is proven to work and would tackle disinformation while preserving freedom of expression, as “Correct the Record” provides transparency and facts without deleting any content.

Avaaz created a mock-up of what this might look on the site factbook.org.

Because of Facebook’s scale, Facebook can’t even fact-check ads quickly enough for a “correct the record” solution to work. Judd Legum posts in a Twitter thread that no amount of clicking “report” in Facebook will guarantee that it will be reviewed:

If there are a lot of reports, or Facebook’s automated systems are triggered, Facebook will put the ad into a cue where third party fact checkers can fact check it IF THEY FEEL LIKE IT

An algorithm is prioritized over people. The perpetual stream of posts coming through Facebook means it’s almost impossible to keep up, to get that fake post in front of real people who can review it instead of algorithms.

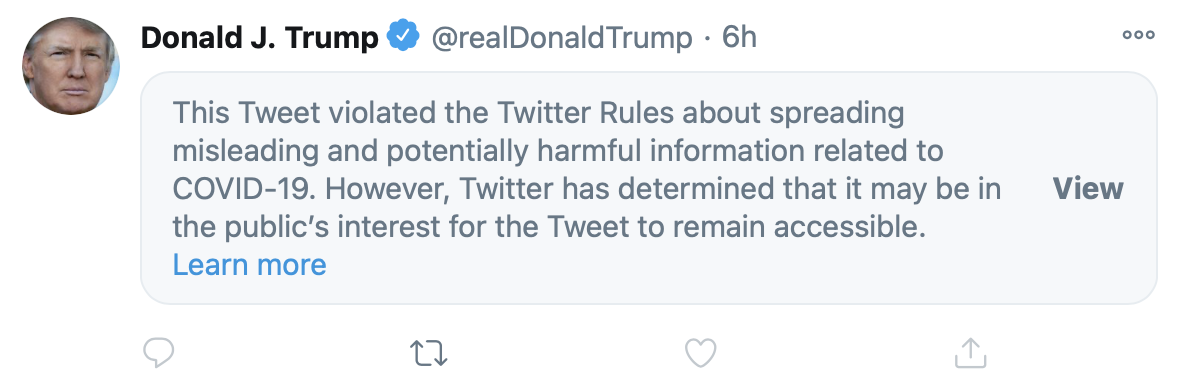

There are exceptions with newsworthy events. In the final weeks of the 2020 presidential campaign, as Trump was recovering from COVID-19 and continuing to downplay the virus, Facebook acted quickly to remove a Trump post that alleged that COVID was “less lethal” than the flu. It was easily fact-checked and clearly against Facebook’s rules against misinformation around COVID-19.

Twitter chose to hide the tweet behind a warning, which also prevents the tweet from accumulating likes and retweets, minimizing its spread:

Twitter has made some additional progress to preempt sharing inaccurate news. In 2020 they experimented with adding a prompt to make sure you’ve read an article you are retweeting:

To help promote informed discussion, we’re testing a new prompt on Android –– when you Retweet an article that you haven’t opened on Twitter, we may ask if you’d like to open it first.

It’s a step in slowing down the spread of misinformation. It could dampen the viral growth of damaging ideas. But this feature is counter to Twitter’s business of engagement and ads. Four years after the 2016 election, when misinformation and political ads ran unchecked, social media companies had done very little to fundamentally rethink their platforms.

Viral spread is a feature of large social networks that can be a double-edged sword. The irony is that some of the features I dislike the most (for example, the viral spread of misinformation or hate) can also be empowering when voices need to be heard.

Black Lives Matter would not have been as impactful a movement if not for massive social media. Shining a light on hateful rhetoric or even physical violence against minorities often starts from individuals whose videos achieve a reach far beyond their usual audience.

And yet the algorithm doesn’t currently know what to amplify and what to make unfindable. Media Matters reported in 2025 on racist videos spreading virally on TikTok:

Users are also posting misleading AI-generated videos of immigrants and protesters, including videos in which protesters are run over by cars. And in an especially dystopian nightmare, AI-generated videos are reenacting marginalized groups’ historical traumas, depicting concentration camps and Ku Klux Klan attacks on Black Americans.

The full report from Media Matters is very disturbing. It’s not just a couple videos that fell through the moderation cracks. It’s many videos and millions of views. TikTok is designed for this.

Infinite content plus viral social platforms is a bad combination. Curation will be nearly impossible as long as social media is designed around likes, reposts, and algorithms. AI is the accelerant to garbage abundance. The best way to stop the spread of hateful content or misinformation is for platform developers to consider that virality is as much a bug as it is a feature.

The government is more attuned to the viral spread of misinformation than ever. In 2021, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy spoke about health misinformation during the COVID pandemic. In a statement and Q&A announcing the guidance, Murthy said:

Modern technology companies have enabled misinformation to poison our information environment, with little accountability to their users. […] They’ve designed product features, such as like buttons, that reward us for sharing emotionally-charged content, not accurate content. And their algorithms tend to give us more of what we click on, pulling us deeper and deeper into a well of misinformation.

The impact of COVID misinformation creeps up on us slowly, as infections climb. The impact of hateful misinformation feels more immediate, such as in gun violence, where very repeated headline is like another stab of heartbreak for those we’ve lost. If the democratization of TV into live-streaming is inevitable, how do platforms do it without incentivizing violence?

There must be balance, letting the good ideas spread while reserving control over the spread of misinformation. There also must be balance between the responsibility of platforms and of the government.

Next: Section 230 →