Mastodon

“We need something that’ll work forever.” — Eugen Rochko

Eugen Rochko rolled out a release of the Mastodon source code quietly in March 2016. He experimented with new features, often things he wanted himself, and it evolved quickly. From the beginning it was kind of a patchwork of APIs. Many of the APIs weren’t new, but they had never been put together this way, with a polished, Twitter-like UI. One major piece was replaced early on, moving from OStatus to the ActivityPub API that we’ll cover in an upcoming chapter.

Mastodon’s strength was as a federated system. There are many instances, each like a mini-Twitter. Instances can talk to each other, allowing replies to be sent to users between instances in a similar way to email sent between email servers.

New instances of Mastodon began to appear. The main instance Mastodon.social steadily grew. As I was launching the Kickstarter campaign for Micro.blog at the beginning of 2017, I received a couple questions about Mastodon as people wondered how Micro.blog might be different.

Then in March of 2017, Mastodon exploded. It spread quickly in part fueled by Twitter changes such as redesigning how replies were displayed.

Writing around that time, Eugen contrasted Mastodon’s approach with Twitter’s in a blog post that fit perfectly into the current pushback against Twitter:

The federated nature of the network also has implications on behaviour. Different instances, owned by different entities, will have different rules and moderation policies. This gives the power to shape smaller, independent, yet integrated communities back to the people.

Mastodon has blocking and muting similar to Twitter, with small differences. These are mostly surface-level changes. More fundamentally, splitting the network over many instances allows each to take a more active role in moderation. User reporting may also be more likely to be addressed on instances that are well maintained.

Sarah Jeong, who had written about the frustration with Twitter’s reply changes, wrote another article for Vice’s Motherboard about Mastodon that underscored the value in having separate instances that were not all controlled as a single, centralized platform:

But Mastodon’s norms aren’t set in stone. And mastodon.social is only one instance in a larger federation. There could be an instance with the fast-paced and hard-edged humor I’ve come to value from Twitter. There could be an instance propagated with news junkies and commentariat.

People were also pulled in because of the perception that Twitter wasn’t doing anything about hate and harassment. If App.net had come along during the backlash against Twitter’s increasingly tight hold on what developers could build, Mastodon was released after the narrative around harassment was clearly defined.

As marketing for Mastodon, its instance-based messaging resonated with people who didn’t think Twitter’s rules were working, or enforced. Wired covered Mastodon’s rise in 2017:

Mastodon has created a diverse yet welcoming online environment by doing exactly what Twitter won’t: letting its community make the rules. The platform consists of various user-created networks, called instances, each of which determines its own laws.

Since then, there have been several waves of new users embracing Mastodon. It has grown to over 2 million users across thousands of instances.

Many people started on the Mastodon.social instance:

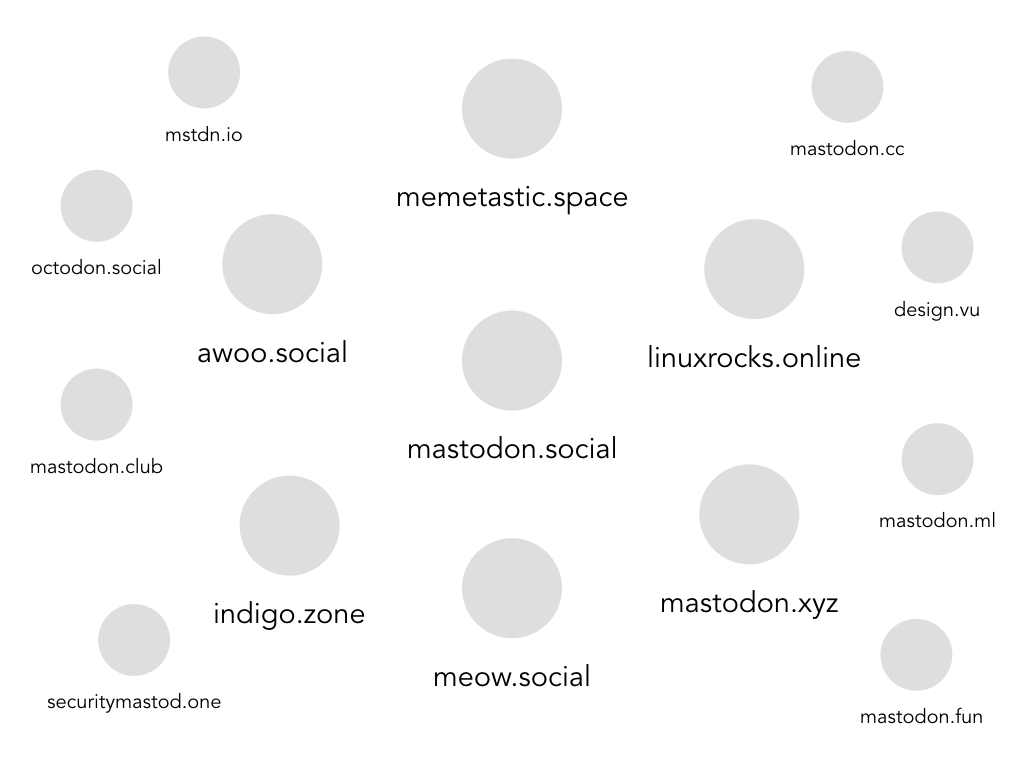

Instances can talk to each other, and a user on one instance can follow a user on another instance. Here are some I picked out from the thousands that exist. Each instance has its own hostname, which is used to form a full username to find someone in the Mastodon federated universe, or “fediverse”:

A full username is constructed with the username on a given instance — which only has to be unique on that one instance — combined with the instance hostname. If my username on Mastodon.social is manton, someone can send me replies across the fediverse using @manton@mastodon.social.

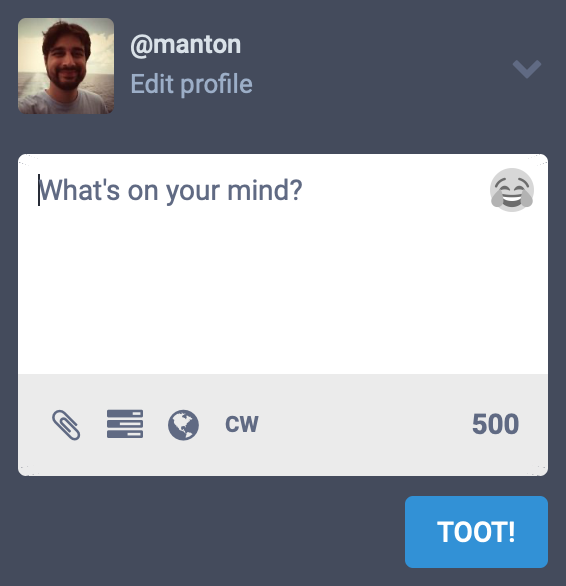

Posting to Mastodon looks a lot like posting to Twitter and other social networks:

That post is delivered to your followers. It also shows up in the “local” timeline of your Mastodon instance. Other users on the same instance can discover your post that way and choose to follow you.

You may have followers on other instances as well. You don’t need an account on those instances. When someone on another instance follows you, your post is sent to that instance so they can see it. It also shows up in the “federated” timeline on that instance, which is a collection of all the posts that instance has seen from the larger fediverse.

For many people getting started with Mastodon, they registered on Mastodon.social, so it quickly became a very large instance hosting most people. Some of the advantages of federation are diminished if users are not spread more evenly across instances, though.

In a 2-year anniversary post, Eugen addressed why so many people are concentrated on a small number of instances:

The 3 largest servers combined host 52% of the network’s users, the 25 largest servers host 77% of all users. This is natural as the largest servers are more known and therefore attract a lot of new people. However, for many people who stick around, they act as gateways, wherein once they learn more about Mastodon, they switch to a different, usually smaller server.

Switching to a smaller instance allows users to find a community that fits their needs better. There can be different community guidelines for each instance.

Instances aren’t usually supported by ads or paid subscriptions. Most Mastodon administrators are donating their time, in some cases supported by donations from members. Crowdfunding can be a useful tool to support running an instance.

The site Run Your Own Social documents how to get started running a small social network based on Mastodon, and why:

The main reason to run a small social network site is that you can create an online environment tailored to the needs of your community in a way that a big corporation like Facebook or Twitter never could.

When an instance has wildly different guidelines in what content they allow, it can create forks in the Mastodon community. Because Mastodon is open source, social network Gab based the new version of their app on Mastodon. Gab was a haven for right-wing topics and hate speech, so Gab was quickly shut off from many other popular instances, breaking federation while still letting Gab function on its own.

IndieWeb co-founders Tantek Çelik and Aaron Parecki talked in the interview in Part 3 about how the idea for the first IndieWebCamp came after what they saw at the Federated Social Web Summit in 2010. Another attendee, Austin King, blogged his notes for other potential standards discussed at the event, from PubSubHubbub to WebFinger, Salmon, and ActivityStreams.

These latter standards would form the initial foundation for Mastodon. Austin wrote in his post about the complicated requirements of the Salmon protocol:

The protocol has been simplified as much as possible, but many technologies have been doomed to obscurity due to the propeller head nature of properly implementing various schemes properly.

Evan Prodromou, who had helped organize Federated Social Web Summit, also built Identi.ca, a microblogging service based on the StatusNet technology whose development he had led. StatusNet would become OStatus, also used in software such as GNU Social, which powered early instances.

OStatus was a suite of protocols, bundling together APIs for notifications, replies, and user profile discovery. As Mastodon was taking off, the Mastodon developer community retooled part of the foundation for Mastodon to replace OStatus with a new API, ActivityPub.

ActivityPub is built on ActivityStream, which outlines keywords that can be used for the social web. Things like an actor (user), note, or reply. The format uses JSON-LD.

Mastodon also had a REST API for building clients. Mastodon on the web was easier for newcomers who were fleeing Twitter to understand, and having the API meant native apps could be built, something users were used to having on Twitter.

The history is a bit tangled, with several forks along the way from Identi.ca, Mastodon, and privacy-focused alternatives to Facebook like Diaspora. Once Mastodon had established itself as the overwhelming “winner” of the fediverse, with more people contributing to standards such as ActivityPub, the fediverse became a stable platform on which other Mastodon-compatible services were built.

Next: Fediverse →