Linkblogging

“These are lean times in social bookmarking. The staff at del.icio.us has been eviscerated by layoffs, and the project is now being run by a skeleton crew. Magnolia, the other useful bookmarking site, has gone offline for the summer while it implements a new ‘don’t irretrievably lose everyone’s data’ feature.” — Maciej Cegłowski in 2009, developing what would become Pinboard

Linkblogging is a form of microblogging that emphasizes linking to other websites. As you’re reading your favorite sites on the web, or following links shared from friends, you blog links to the articles that are noteworthy. Optionally you add some short commentary, but the focus is mostly on the title or quote from the web page you’re linked to. The link away from your own blog is the most important piece.

Rebecca Blood wrote about this format in The Weblog Handbook:

…for these folks it seemed the most natural thing in the world to put the record of their travels around the Web on the Web, and so a particular type of website was born. Enthusiastic surfers turned their home pages into a running list of links with descriptive text to inform their readers why they should click the link and wait for the page to download.

HTML is well-suited for the linkblog format. Snippets of HTML can have inline links, block quotes, or a photo preview. These kind of fragments work great in a timeline-like, reverse-chronological blog format, but they could work equally well assembled into newsletters. If there’s audio, they could be assembled into a podcast feed.

Whether it’s a web page of multiple posts, a newsletter, or linkblog posts in a feed reader, each component of the whole is its own self-contained HTML fragment. Using HTML gives us the most portability and reuse across platforms.

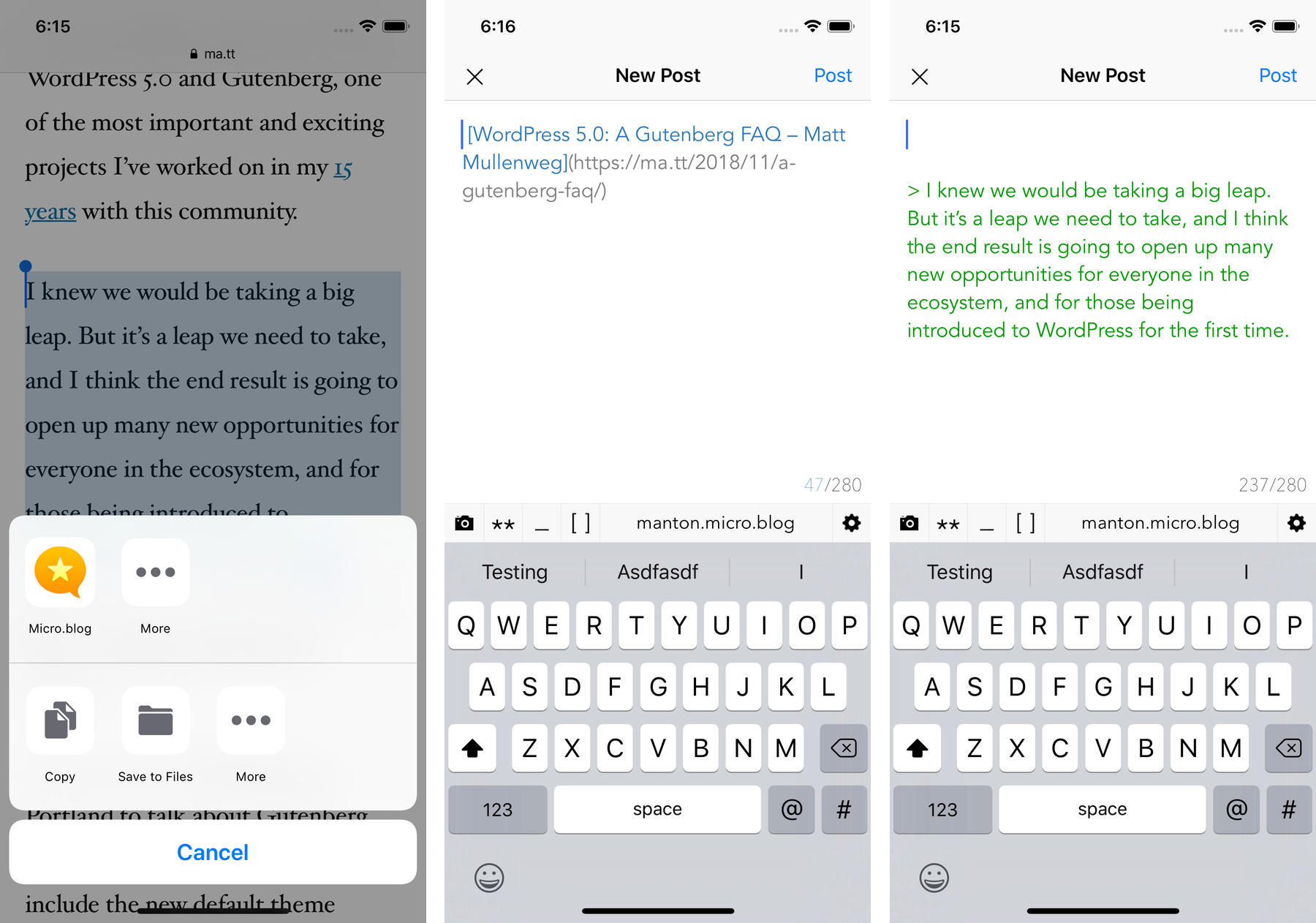

Many bloggers who regularly post link-style posts try to automate the posting so that it’s as easy as possible when they run across an interesting article. Micro.blog has a web browser bookmarklet for this. The iOS app for Micro.blog also supports sharing links from other apps:

The draft post can include a link and title, and optionally the selected text from a web page to use as a quote.

Half of Daring Fireball is structured as a linkblog. It’s so successful that John Gruber’s approach to linkblogging has been copied by many other sites. MacStories, Six Colors, One Foot Tsunami, John Moltz’s Very Nice Web Site, and Marco Arment’s blog are just a handful that follow this pattern. All of these sites post the occasional essay, but most blog posts link away to an external site in the RSS item, not back to their own site.

At a technical level, this difference can best be seen in the RSS feed’s <link> and <guid> elements. These elements will contain URLs that either link back to the main site, or link away to an external site.

Here is where this evolving approach to link blogs starts to break down. Let’s take an example from Six Colors, one of my favorite sites. In a link post about Hulu’s pricing, Jason Snell actually writes 4 paragraphs of commentary (plus a footnote). This is more like an essay than a short link post that points to the external site.

Another example is when MacStories linked to Twitter’s launch of Moments. A few paragraphs of quoted text, 5 paragraphs of MacStories commentary. The commentary is as important or even more important to read than whatever Federico is linking to.

Sometimes we read sites like MacStories, Six Colors, or Daring Fireball more for the commentary than for what is being linked to. But when using an RSS reader, there is too much confusion about where an item’s link goes when clicked if the site’s feed isn’t consistent about linking everything back to its own site.

And in fact Jason Snell acknowledges this problem by offering two separate RSS feeds: the default one, with a mix of links back to Six Colors for essays and pointed elsewhere for link posts; and another feed with everything linking back to Six Colors, where the commentary lives. He also attempts to minimize confusion on his own site by giving each type of post its own icon in the site design.

The less clear-cut the distinction between essays and link posts, the more confusion we introduce to readers. In some ways, this mixed approach really only works for Daring Fireball, because his feature essays are so long, and so obviously different in format to the rest of the link posts.

Good conventions for blogging have been at a standstill for years. While part of the appeal of indie blogging is there’s no one “right” way to do it, and authors can have a strong voice and design that isn’t controlled by a platform vendor, we must accept that Twitter has taken off because it has a great user experience compared to blogs. It’s effortless to tweet and the timeline is consistent. For blogging to improve and thrive, it should have just as straightforward a user experience as social networks wherever possible.

Luckily, RSS already has everything we need for clients to visually distinguish between link posts and regular ones. If the <link> element points to a domain other than the one for the site, it’s probably a link post. If the <link> and site domain match, it’s a full post.

I’ve adopted this in Micro.blog by exposing the domain in the UI itself, at the end of the title or microblog post whenever it’s a link post. If it’s a full post, the link isn’t added. And for either type of post, the timestamp links back to whatever was in the <link>.

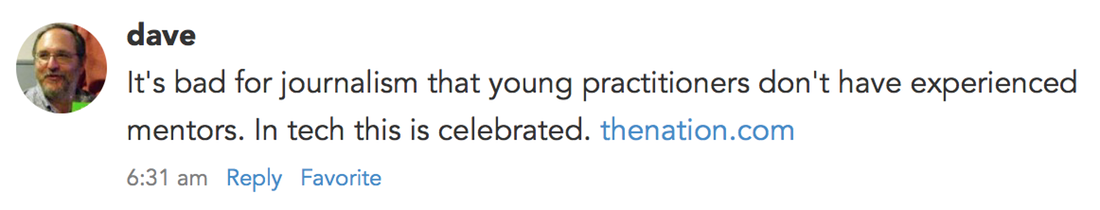

Here’s a screenshot from one of Dave Winer’s posts. Note that the link was not in the RSS text. It was added by Micro.blog automatically:

All of this boils down to two simple recommendations:

- If you’re a blog author and you’re adding any significant commentary, the RSS or JSON Feed should point back to your site.

- If you’re an RSS client developer, the difference between link posts and full posts should be exposed in the UI.

I believe that adopting these will bring more consistency to blogging. Users won’t need to hover over links, or guess what will happen on a click or tap. It’s a small change that will make reading blogs a little better.

Bloggers using linkblogs are reading web pages and linking to the ones they find interesting. Chris Aldridge thinks there should be more emphasis on the reading part of composing a linkblog post, suggested linkblogs could be renamed “reading pages”:

On today’s more advanced web, there’s actually more value in naming it a reading page as it indicates a more proactive interest in the bookmarked content–namely having spent the time, effort, and energy to have actually read the thing being bookmarked.

Linkblogs are essentially a convention for attribution. Even just an author name and link make the web a little better and more resilient to linkrot, because the reference persists even when a linked web page is lost.

Micro.blog has deep support for bookmarks and blogging about books you’ve read. It integrates with IndieBookClub, which is built on the IndieWeb building blocks Microformats and Micropub. Micro.blog also leverages Quotebacks for its “embed” feature to make it easier to quote a microblog post.

Quotebacks were introduced by Tom Critchlow and Toby Shorin in 2020 as a way to bring the ease-of-use of social networks “embed” features to the rest of the web. Introducing Quotebacks, Tom wrote:

The ultimate goal is to encourage and activate a deeper cross-blogger discussion space. To promote diverse voices and encourage networked writing to flourish.

Cross-site discussions is a recurring theme in this book and has multiple facets. There’s making posting easier, with Micropub and more feature-rich platforms. There’s Webmention, for notifying blogs when a reply is posted. And there’s the foundation of HTML and Microformats

Without HTML, we could never have diverse blog formats because a more narrow structure of linking (like the Twitter API) would trend toward centralization and monoculture. Linkblogging and Quotebacks fit perfectly into the vision of a hyperlinked, distributed conversation across the web.

Next: Interlude: Interlude: Interview with Om Malik →