Atmosphere

“If fate doesn’t exist, then we must create it.” — Jay Graber

There were a series of fascinating decisions that all seemed to happen at once. Elon Musk was buying up Twitter shares. Jack Dorsey was stepping down as Twitter CEO. And Jay Graber, who was on the early group coming up with what Bluesky would look like, was asked to lead Bluesky. She said she would lead it on one condition: if they could spin out Bluesky into its own company independent of Twitter.

That moment has completely changed the trajectory of the social web. Jack Dorsey’s original vision was to build an open protocol that could power Twitter itself. That idea was crumbling as Elon reshaped Twitter into X, but in its place was built something arguably stronger: a new company independent of the past.

As of this writing, Mastodon has grown to over 10 million user accounts. While smaller than mainstream platforms like Threads, which could leverage Instagram’s huge user base to catapult past 100 million users, there was a sense that Mastodon and ActivityPub had a clear lead as the solution for the social web. When Bluesky launched, there was pushback about why the world needed Bluesky’s AT Protocol when ActivityPub already had so much traction. Surely Bluesky was far behind and could not catch up to Mastodon.

Propelled by more users leaving Twitter when Elon Musk acquired the company, and also users from Brazil when Twitter was temporarily banned there, Bluesky not only caught up but surpassed the fediverse user base, reaching 50 million users. Bluesky was closer in design and spirit to early Twitter. Although it used a distributed protocol, there was initially no choice of signing up on a different server, so less onboarding confusion, making the application feel more approachable to new users.

It is becoming easier to self-host an AT Protocol personal data server (PDS). A PDS is part of the AT Protocol architecture that stores your actual data: posts, likes, even who you’re following. This is all public data and can be moved across hosting providers, conceptually similar to migrating blog post data when moving your domain name.

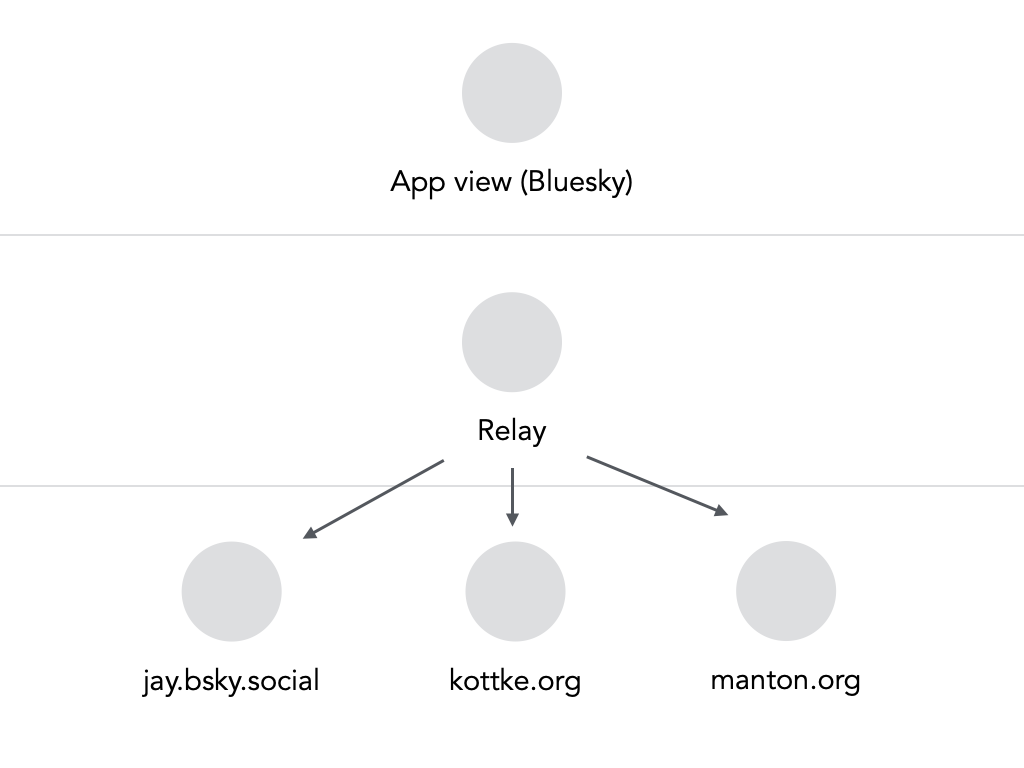

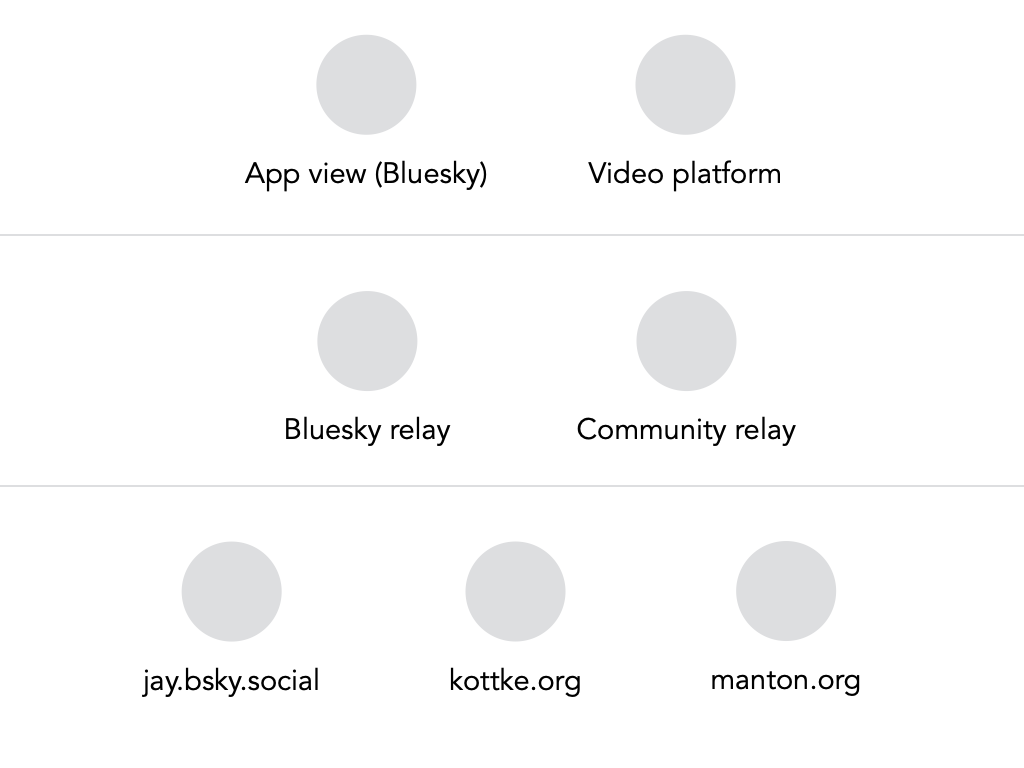

The other parts of AT Protocol are the relay and app view. The relay gets posts from each PDS and routes the posts across the network. The app view sits at the top, storing the collection of posts in a way that can fit into the timeline and feeds, and providing the user interface. Moderation decisions are also largely implemented at the app view layer, which means different app views can apply different rules to the same data.

Just as you don’t lose your domain name identity when moving your blog, you don’t lose your Bluesky username when you move to a new PDS. This is one of the most visible differences between Bluesky and Mastodon. On Mastodon, most people join a server that has a domain name managed by the server administrator, and everyone on that server has an identity on the fediverse that is shared.

There is resilience in replacing the other larger components of the architecture. You could add new apps views, for example one focused only on video content. And you could clone and replace Bluesky if something happened to the company, or it was taken over by new leadership. So the architecture is modular.

Paul Frazee, Bluesky’s CTO, blogged in late 2025 about the atmosphere as a way to bridge small and large clouds with the same architecture, something that scales from personal servers to large networks like Bluesky:

The reason that Substack found its feet is the same reason I care about Atmospheric sites: because it’s a space that people really own. If you self-host your account and your site, you can get kicked off every app in the Atmosphere but you’ve still got that identity and that presence. Even as somebody that works at Bluesky and believes in good moderation, I think it’s a good idea to have that kind of check on the social apps' power.

Bluesky posts are limited to 300 characters. This is enforced by a schema for data called lexicons. Lexicons are defined with JSON:

{

"id": "app.bsky.feed.post",

"defs": {

"main": {

"type": "record",

"record": {

"required": ["text", "createdAt"],

"properties": {

"text": {

"type": "string",

"maxGraphemes": 300

},

"facets": {

"type": "array",

"items": {

"type": "ref",

"ref": "app.bsky.richtext.facet"

}

}

}

}

}

}

}

Instead of Markdown or HTML, Bluesky uses rich text facets for character ranges of linked text. This can be clunky to work with for developers, and makes Bluesky posts feel more apart from the HTML-based open web than necessary, but it’s optimized for performance. There is no need to parse the text for links, new facets can be added later without breaking anything, and the fallback is always plain text.

In a microblog post, a facet for a hyperlink looks like this:

{

"text": "Hello Manton!"

"features": [

{

"uri": "https://www.manton.org/",

"$type": "app.bsky.richtext.facet#link"

}

],

"index": {

"byteStart": 6,

"byteEnd": 11

}

}

While Bluesky defines the microblogging lexicon, anyone can publish a new lexicon for other types of data, such as for an Instagram-like photo timeline or for long-form blog posts. Data using other lexicons will co-exist with Bluesky-specific data in someone’s PDS.

Leaflet has emerged as a popular blogging app based on AT Protocol. They’ve published their lexicon for long-form posts that others can adopt. There is also a more general lexicon in Standard.site:

Standard.site began as a conversation between developers building long-form platforms on AT Protocol. Each had working implementations. Each had defined similar schemas. Coordination was the missing piece.

This new lexicon’s first focus is on metadata. It leaves the actual content definition — whether Markdown, HTML, or the structured block-based format that Leaflet uses — to individual platforms.

I have high expectations for Bluesky and the AT Protocol. Using domain names for usernames aligns it with the IndieWeb, even though the AT Protocol is more complicated than IndieWeb APIs.

Bluesky is also bringing the AT Protocol to the IETF, so that long term it can be managed by a standards body:

We want AT to have a neutral long-term home, and the IETF seems like a natural fit for several reasons. It’s the home of many internet protocols that you know and use every day: HTTP, TLS, SMTP, OAuth, WebSockets, and many others. The IETF has an open, consensus-driven process that anyone can participate in. And importantly, the IETF cares about both the decentralization of the internet while also keeping it functioning well in practice. This balance between idealism and pragmatism matches how we’ve approached the challenges of building a large-scale decentralized social networking protocol.

The Bluesky team is well funded and moves quickly. You can see their principles of openness and care for the web in many decisions, including that some of the Bluesky APIs are public, not needing authentication. Bluesky’s openness and ability to scale to many people, even those we may disagree with politically or culturally, is a fitting complement to Mastodon, which often looks inwardly, focused on smaller communities and consent for data to the public.

Mastodon appears to have grown stagnant. I believe it has accomplished what founder Eugen Rochko set out to do. Eugen deserves enormous credit for all the progress helping the open web move forward. But perhaps the project no longer has a clear vision for where to go next.

In 2025, Eugen resigned as Mastodon’s CEO, handing the project off to others under a non-profit foundation:

Mastodon is bigger than me, and though the technology we develop on is itself decentralized—with heaps of alternative fediverse projects demonstrating that participation in this ecosystem is possible without our involvement—it benefits our community to ensure that the project itself which so many people have come to love and depend on remains true to its values.

Another part of Eugen’s post particularly resonated with me:

I think I need not elaborate that the passion so many feel for social media does not always manifest in healthy ways. You are to be compared with tech billionaires, with their immense wealth and layered support systems, but with none of the money or resources. It manifests in what people expect of you, and how people talk about you.

I have felt this because for all Mastodon’s success, it brings new problems. Some of the most unexpectedly personal and harsh replies I’ve ever received have come from Mastodon folks who think they’re fighting the good fight. When people are sure they are on the side of justice, they justify extreme rhetoric, even dehumanization of people on the wrong side. The focus on smaller communities is a double-edged sword: good in the move for decentralization and to focus more on community moderation, but also amplifying the negative effects of filter bubbles.

When I quit Twitter in 2012, I remember noticing for the first time how influential it had been to have a community of peers that shaped popular opinion. After I stopped reading Twitter, when Daniel Jalkut and I would record Core Intuition, I would often come to the show with a different perspective than what our Mac and iOS developer community on Twitter had already decided was best. That didn’t mean I was right more often, but I was happy that it felt like my opinion was my own.

It’s easy to look at many Mastodon servers now and see what the groupthink is and how it affects discourse. It’s often political or cultural, which means in today’s climate it’s divisive.

The civility problem combined with slow growth should be worrisome to the fediverse community. From FediDB, there seems to be a decline in active users. That trend will continue without some kind of event to shake things up, like the influx of Twitter users a few years ago. Bluesky is now much larger than Mastodon because it has managed to break into the mainstream social web, more approachable for new users.

In a great interview with Jon Henshaw, Eugen talked about appealing to people dissatisfied with US-based companies:

People no longer want to rely on US tech companies, especially if they live in Europe, Asia, or anywhere else on Earth. And what Mastodon and the fediverse offer is a social media platform in your country, local to you, not subject to whatever is happening in the US or to any third-party developers of the software.

This matches my own experience running Micro.blog, which is why we added European web servers. Whether on the fediverse or the IndieWeb, people want ownership of their content and their connections with others. That isn’t likely the path to significant growth for the fediverse, though, as it introduces more complexity in choosing where to sign up.

I believe Mastodon will be around for many years to come. Can it be a healthy community for newcomers, or will it remain an opinionated niche in the social web?

If 2025 was about the fediverse — with new activity from Ghost, Flipboard, WordPress, and also newer platforms — I think 2026 and beyond will be a partial reset to the IndieWeb. More blogs. More independent voices. More platforms and bridges that span multiple protocols. And of course Micro.blog is well positioned for this future because those were our founding principles all along.

Bluesky and the AT Protocol will not replace indie blogs. Instead, the atmosphere could become a layer of sync infrastructure for larger platforms.

When Elon Musk acquired Twitter, he imagined X as a town square, a place that prioritized freedom of discussion. But too many communities have felt completely unwelcome on X, marginalized by the lack of moderation, and alienated by a shift to the political right led by Elon himself. The result is social media that is slanted more than ever to the sensational, to picking fights instead of learning from the diversity that everyone brings to the web.

That does not mean there isn’t value in public feeds and global search, if run with the resources of a larger platform. AT Protocol was designed for this. As we move our content to our own domain name, embracing blog workflows, a larger open platform can still benefit us in discoverability and connection.

Next: Part 6: Community →